Welcome!

Cheryl Sawyer welcomes readers to her historical novels, blogs about discoveries in writing and research, and shares her experiences in the world of creative fiction. Cheryl has had a long career in book publishing, which she left in 2014, to write full-time. Her first historical novel was published by Random House in 1998 and her American debut in 2005 was acclaimed by Booklist as 'a grand and glorious delight'. More novels have been released in several languages by Penguin US, Bertelsmann, Mir Knigi, Via Magna, Domino, Reader's Digest and Endeavour Press UK. Cheryl Sawyer's work has been longlisted for awards by the Historical Novel Society and the American Library in Paris. She has recently completed an English Civil War trilogy with The Winter Prince, Farewell, Cavaliers and The King's Shadow. Peter James calls her work ‘historical fiction writing at its very best’.

Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, from Holland, early 1737

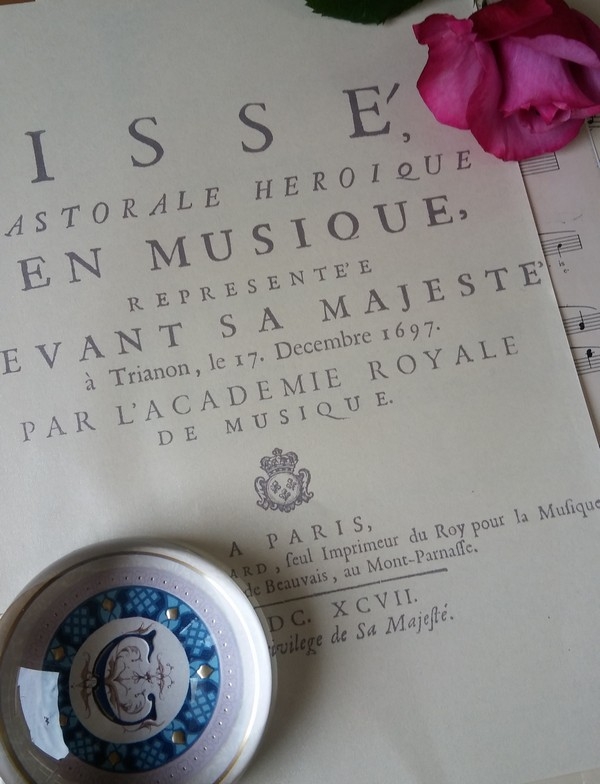

Émilie du Châtelet’s favourite opera composer was Destouches, and Émilie loved to play and sing his Issé at the harpsichord. She often gave the whole opera for guests. It’s unlikely that she would have felt like singing, however, had she seen this letter written by Voltaire while she waited for him to return to France. It sounds as though Holland suits him much better than Cirey.

The Crown Prince has commanded Count Borck, ambassador for the King of Prussia in England, to offer me his house in London, should I wish to go there, as rumour has it at present; however I’m being treated here very much better than I deserve. The bookseller Ledet, who has earned a little by publishing my feeble works, and who is now bringing out a magnificent edition, shows his gratitude to me in much greater measure than Paris shows its ingratitude. He insists that I stay with him when I go to Amsterdam to see how Newtonian philosophy is faring. He has chosen to place the head of your friend Voltaire on his masthead. Due modesty prevents me from telling you in all sincerity what boundless consideration I’m shown in this country.

I don’t know what impertinent rag, wretched echo of the wretched news penned in Paris, took upon itself to say that I’ve fled abroad so I can publish without licence. I’ve denied this fabrication in the Gazette d’Amsterdam by disowning everything of the sort that’s been printed in my name, whether in France or abroad. I acknowledge as mine only works that have received a royal licence or official authorisation. I’ll confound my enemies by giving them no hold on me, and I’ll have the consolation that whoever wants to harm me will have to lie outright …

In the breaks allowed from philosophy I’ve been correcting all the poems I’ve written from ‘Oedipus’ to ‘The Temple of Friendship’. There will be several addressed to you: over these I’ll take greater care.

From Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, February 1737

On the day when we first recorded the soundtrack of the concept film, Émilie & Voltaire: left to right, Nicholas Gentile, moi, Julie Lea Goodwin, Robert McDougall.

Poor Émilie, she wasn't smiling when she wrote to their friend d'Argental in February 1737!

'I’ve received his letter written on the 10th. He drank some milk that made him ill; he wasn’t well when he wrote. He tells me it’s all over the press in Holland that: ‘The Dutch ambassador in Paris reckoned there was an order out to arrest Voltaire wherever he might be’; that he’s been in the news there for a month; and everyone wants to see him. He’s gone to Amsterdam: he’s in despair about all the above, and he’s right to be so. But he’s still determined to have his Philosophy printed in Holland: he says everyone will then know exactly where he is, if they don’t already; and at least it will be seen why he’s gone there, which can only be for the best. Here’s his address: write to Messieurs Ferrand and d’Arty, merchants, Amsterdam, and no other name: it’s a secure address.

'In the name of friendship, exhort him to issue the Philosophy in Paris first, and to cut out the chapter on Metaphysics. If he wants to have it printed in Holland, he must at least send the manuscript to Paris at the same time—then he won’t look as though he’s trying to bypass the Censor …

'A last thought … let alone France, I’m not even sure that he’s safe in Holland! I don’t know whether you have any reassurances for me on that point—you’ll think I’m mad, and I shortly will be. I’m like a miser whose whole fortune has been snatched away, terrified that at any moment it’ll be tossed into the sea.'

Émilie & Voltaire--the concept film

How to write an Australian opera--with dogged assistance. Excited to be shooting the concept film in November. Follow our progress on Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/emilieandvoltaire/

Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thiriot, from Leyden, early 1737

At last I have more of Voltaire's letters! This one comes while Émilie is tearing her hair out at Cirey, terrified that Voltaire will never return to France. Meanwhile he is writing from Holland to his friends. Does the last paragraph of this passage bode well for Émilie?

It’s true, my dear friend, that I’ve been very ill, but the liveliness of my temperament makes up for my lack of strength; my delicate nervous energy may send me to the grave, but it speedily snatches me out of it. I’ve come to Leyden to consult Doctor Boërhaave about my health, and s’Gravesande about the philosophy of Newton.

Prince Frederick of Prussia showers me every day with admiration and gratitude; he deigns to write to me as to a friend; he’s sent French verses to me that are the equal of those written at Versailles in the days of good taste and fine pleasures. It’s a pity that a prince like him has no rival.

I never forget to slip a few words about you into all my letters. If my tender friendship for you can be of any use, won’t I be all the happier? I live only for friendship: that is what kept me at Cirey for so long; that is what will take me back there, if I return to France.

Maupertuis: a threat to the paradise of Cirey?

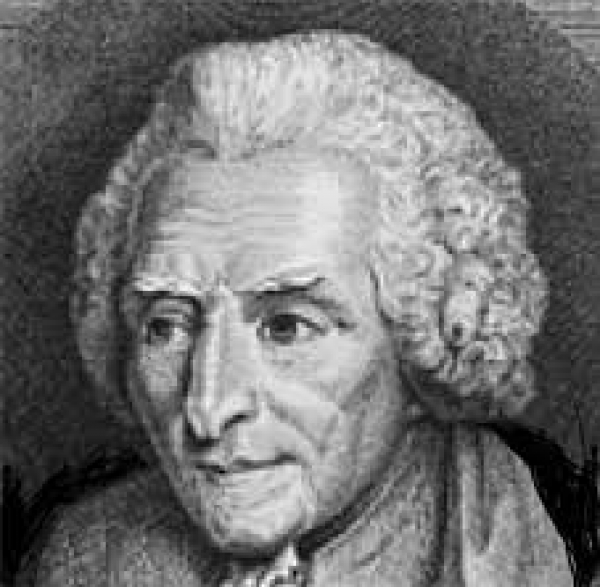

Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis was a famous mathematician and physicist whose achievements are all familiar to scientists today. He is also part of a love triangle with Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet, in the opera Émilie & Voltaire that Nicholas Gentile is developing to my libretto and with the generous sponsorship of Fine Music Sydney, Andrew Su, the City of Melbourne and the major sponsor, Opera Australia. Maupertuis's role in the short opera film of the same name is played by brilliant tenor, John Longmuir. More in this blog when we have completed the film!

Maupertuis was born in the picturesque seaport of Saint-Malo in Brittany. His father was one of its important shipping merchants known as corsairs, who also practised as privateers against foreign vessels and even as pirates. The vast wealth that Monsieur Moreau earned from the sea passed to his son, and so did his noble name, de Maupertuis, granted to the family by King Louis XV not long before Pierre-Louis was born.

Maupertuis received an excellent education. Like many active young men of the nobility he became an army officer, but he soon discovered that his real interest was mathematics. Being rich, energetic and clever, he could make his own choices in life. He went to Basel, Switzerland, to study with the great mathematician, Daniel Bernoulli. Maupertuis proved to be an original thinker, his work was widely read and in 1723 he was admitted to the French Academy of Sciences.

Maupertuis was a Newtonian: that is, he believed with Englishman Isaac Newton that the movement of the spheres in the universe operates according to forces such as gravity, and that the laws of nature can all be expressed in the language of mathematics. This put Maupertuis in opposition to most of the Academy, who supported the theories of the Frenchman, Descartes.

Scientific debate was also fashionable in the Paris salons, where Maupertuis was a favourite because of his sparkling intelligence, his wit and his success with the ladies. In 1733, Voltaire began to take lessons from Maupertuis in mathematics, and they became friends. Voltaire, deeply in love with the beautiful and learned Émilie du Châtelet, hired Maupertuis as her mathematics tutor also. Rumour had it that Maupertuis briefly became her lover, though he played somewhat hard to get, and they parted when Émilie left Paris in 1735 to live with Voltaire at her Château de Cirey in the remote Champagne region.

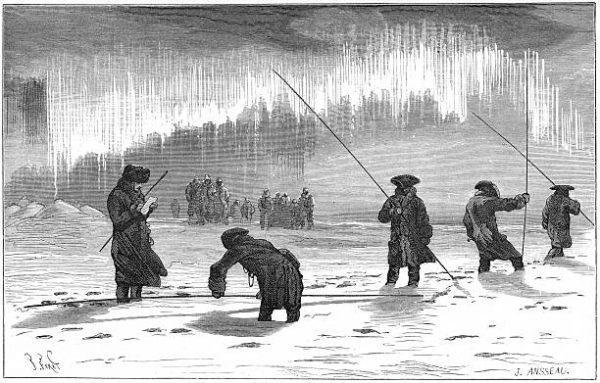

Then came Maupertuis’s great expedition, which made him famous in France and throughout the scientific world as ‘the man who flattened the Earth’. In 1736 he led a team of scientists and surveyors to Lapland under royal commission, to prove Isaac Newton’s theory that the Earth is not a perfect sphere, but is relatively flatter at the Poles.

From Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, February 1737

Poor Émilie! Stuck at Cirey while Voltaire is in Holland having some of his most controversial works published--because they were refused by the French royal censor. Today I should be bringing you a letter from Voltaire (I'm alternating their letters between 1735-38, to give you the pattern of their lives) but at the moment, because of coronavirus lockdown, I have no access to V's letters in French. If you know where I can access them online, kindly send me a bulletin on my Contact page! Meanwhile I'm translating extracts from Émilie's letters, in chronological order, more or less weekly.

I’m not going to suggest that Voltaire returns just to put himself into hiding as the ministry requires. For as long as they want him to return incognito, and insist that no one must know where he is, he’s in danger. Now, if he’s to run any kind of risk, how can I possibly be the one to ask him to come back? Besides, it’s impossible to keep him hidden where absolutely no one can find him. Concealment is a humiliating procedure that he will never consent to: it makes him look guilty, plus he’s well known in these parts, and wherever he happens to live, he always draws attention.

There are priests and monks all around us; he’s adored by honest folk in the province but there are also bigots here, as everywhere. In short, if he’s to be genuinely safe, it can’t be known that he’s at Cirey—it’s useless even considering it.

I did suggest to you at one stage that we might get him back and make sure his return is not publicly known, but I’ve no confidence that it could be kept from the minister; and if he were discovered and ran risks in consequence, how we would reproach ourselves! Moreover, what a triumph it would be for our enemies, to know that he was trying to hide himself away! I repeat, it’s too humiliating and he’d never consent to it. What I wanted was for him to stay at Cirey without anyone being aware—that is, without his sending any letters, and without his return being bruited about Paris; but that was when I thought he might do so without any danger of being caught—I could never ask anyone to run that kind of risk.

I feel as though I’m going to lose him precisely because I want to save him, and thus die from grief. But I’m also appalled by the thought of his coming back solely for my sake—and I could never give him any advice that would make him sorry for having followed it! I prefer to see him free and happy in Holland than living the life of a criminal in his own country. I’d rather die of grief than tempt him into a false step.

From Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, Paris

Voltaire dedicated his Metaphysics to Émilie and sent a copy to her with this verse:

Of the author of Metaphysics, beware:

He’s on his knees before you.

He ought to be burnt in the town square

But he only burns for you.

While Voltaire is in Holland in early 1737, Émilie is beside herself about this very work. She writes to their friend d’Argental:

In his letter of the 8th he sends me a copy of his letter to the Crown Prince of Prussia, that is all very well and all very prudent, but look what I find: ‘I shall be bold enough to send Your Royal Highness a manuscript that I would only show to someone with a mind as free of prejudices as your own, and who, amongst all the praises one may bestow, are worthy of boundless trust.’

I know this manuscript: it’s his Metaphysics, so replete with reason that it would send him to the stake, a book that’s a thousand times more dangerous—and certainly more actionable—than La Pucelle [Voltaire’s risqué poem on Joan of Arc]. Imagine how it shook me; I still haven’t got over my astonishment—or, may I tell you, my anger. I sent him a furious letter; but it will take so long on the way that the manuscript may have gone off before it gets to him, or at least he’ll be able to claim it has—because sometimes we are carried away, and the demon called reputation (his view of which I do not share) never leaves us alone.

I must tell you I couldn’t help lamenting over my fate, when I saw how little the tranquillity of my life must mean to him. In future I shall be always fighting against him for his own good, but without being able to save him. In his absence, I’ll be either trembling for him or lamenting over his faults. But in the end, that is my destiny, and it’s dearer to me than the happiest of futures. You must help me to parry this latest blow, if it can be done, because sooner or later his imprudence will destroy him for ever. The Crown Prince can no more keep this particular secret than he can himself.

From Voltaire to Frederick, Crown Prince of Prussia

At the beginning of March, I posted a letter from Madame du Châtelet as part of the correspondence written by herself and Voltaire from 1735 to 1738, all of which I selected and translated. I am now in lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic and I have Émilie’s correspondence on my desk--but Voltaire's has been returned to storage at the Fisher Library at Sydney University. Online searches cannot restore it to me (he wrote 15,000 letters after all!). Here is my solution. I have access to a selection of his letters: Voltaire in His Letters by S.G. Tallentyre (G.P. Putnam Sons, 1919) and it is out of copyright. For now, why not bring you Tallentyre's translations from Voltaire's side and mine from Émilie’s?

The letter I posted in March was from Émilie to the Comte d'Argental in 1737, desperately lamenting Voltaire's departure to Holland. She was terrified that he would succumb to the blandishments of the 'philosopher prince', Frederick of Prussia (later Frederick the Great) and go to Potsdam. So it's Voltaire's turn: here is some of a letter to Frederick written at that time, with translation by Tallentyre.

I examine man. We must see if, of whatsoever materials he is composed, there is vice and virtue in them. That is the important point with regard to him—I do not say merely with regard to a certain society living under certain laws: but for the whole human race; for you, sir, who will one day sit on a throne, for the wood-cutter in your forest, for the Chinese doctor, and for the savage of America. Locke, the wisest metaphysician I know, while he very rightly attacks the theory of innate ideas, seems to think that there is no universal moral principle. I venture to doubt, or rather, to elucidate the great man's theory on this point. I agree with him that there is really no such thing as innate thought: whence it obviously follows that there is no principle of morality innate in our souls: but because we are not born with beards, is it just to say that we are not born (we, the inhabitants of this continent) to have beards at a certain age ?

We are not born able to walk: but everyone born with two feet will walk one day. Thus, no one is born with the idea he must be just: but God has so made us that, at a certain age, we all agree to this truth.

It seems clear to me that God designed us to live in society—just as He has given the bees the instincts and the powers to make honey: and as our social system could not subsist without the sense of justice and injustice, He has given us the power to acquire that sense. It is true that varying customs make us attach the idea of justice to different things. What is a crime in Europe will be a virtue in Asia, just as German dishes do not please French palates: but God has so made Germans and French that they both like good living. All societies, then, will not have the same laws, but no society will be without laws.

From Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, Paris, February 1737

I knew your prudence would suggest that Voltaire wouldn’t be safe from the minister [Chancellor de Fleury] if he returned to France [from Holland]. Even so, couldn’t he come to Cirey? It’s the Champagne country house where you’ll see the fewest people in the province, and it’s the most respectable place for me: if he were hidden elsewhere I’d be visiting him often and that would look odd and cause talk …

If he’s not at Cirey I won’t be able to monitor his conduct closely enough, and the kind of wisdom he needs at this stage of his fortunes can only be achieved by showing him the abyss that lies before him at every second …

I’ve just now received a letter that makes me terribly afraid he won’t return at all. I’m devastated. I have to confess that I’m very afraid he’s being as treacherous to me as he’s been towards the minister. Anyway, we’ll see if he comes back; but once again I don’t believe he will, and seriously I don’t possess the strength to survive the grief of it. I’ve done nothing wrong; the sad consolation is that I wasn’t born to be happy. I hardly dare to ask anything more of you, or else I’d beg you to make one last attempt to sway his heart. Tell him I’m very ill; that’s what I’m telling him myself—that he owes it to me to come back and save me from death. This is no lie; I’ve had a fever for two days and the violence of my imagination is sufficient to kill me in four …

If, as you say yourself, his happiness in life depends on the wisdom with which he acts at this point, we mustn’t lose sight of him for a moment. You wouldn’t blame me if you’d seen his last letter: he signed it and called me ‘Madame’. The difference was so shocking, I almost fainted with the pain. Write to him at Brussels!

From Voltaire to Frederick, Crown Prince of Prussia, 1 January 1737

Monseigneur, I shed tears of joy on reading the letter of 9 November with which Your Highness was good enough to honour me. In it I recognise a prince who will be the beloved of mankind. I am filled with amazement. You think like Trajan, you write like Pliny and you speak French like the best of our writers. What a difference between men! Louis XIV was a great king and I respect his memory, but he did not think with your humanity, Monseigneur, nor was he your equal in expression. I’ve seen some of his letters. He could not spell his own language. Under your auspices, Berlin will be the Athens of Germany and may become that of Europe.

Here I am in a town [Amsterdam] where two humble individuals, Mr Boerhaave on the one hand and Mr ’s-Gravezande on the other, attract four or five hundred foreigners [to hear their lectures on physics]. A prince like you ought to attract many more, and I want you to know that I would consider myself very unfortunate if I did not see the epitome of princes and the wonder of Germany before I die. I do not seek to flatter you, Monseigneur—that would be a crime. It would be like blowing poison on a flower, an act of which I am incapable. It is from my grateful heart that I speak to Your Royal Highness.

From Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, Paris, December 1736

Dear guardian angel of two unfortunates, at last I’ve received news of your friend from the border; he arrived without accident and is in good health [Voltaire fled France into Belgium on 22 December to escape outrage over a new, controversial poem, ‘The Man of the World’]. His fragile health doesn’t suffer so much when he’s travelling because he does less work. Nonetheless, when I look out at the ground covered in snow, at this dark and heavy weather, and when I think of the climate into which he’s headed, and his dreadful susceptibility to the cold, I’m ready to die of misery. I could endure his absence if I weren’t so worried about his health …

As soon as you receive this letter, write to him as Monsieur Revol, merchant, at Brussels. From there he goes to Amsterdam, where they’re to print a complete edition of his Works … but his main concern is that no one should know he’s in Holland. Everyone must be led to think he’s gone to Prussia …

I’m absolutely against his going to Prussia and I’m begging you on my knees—he would be lost in that country, he’d go for months without my getting any news of him; I’d die of anxiety before he could return. The climate there is terribly cold …

His affairs are not so desperate, and you’ve been encouraging me to think they’ll be settled within a few months, so why go so far? In spring I could see him again at the court of Madame de Lorraine [at the palace of Lunéville] or wherever she happens to be, or on the estate of a third party—because there are no orders out against him to prevent it. This hope keeps me alive; if you take it away, you’ll kill me.

Apologies for the poor quality of the portrait of d'Argental.

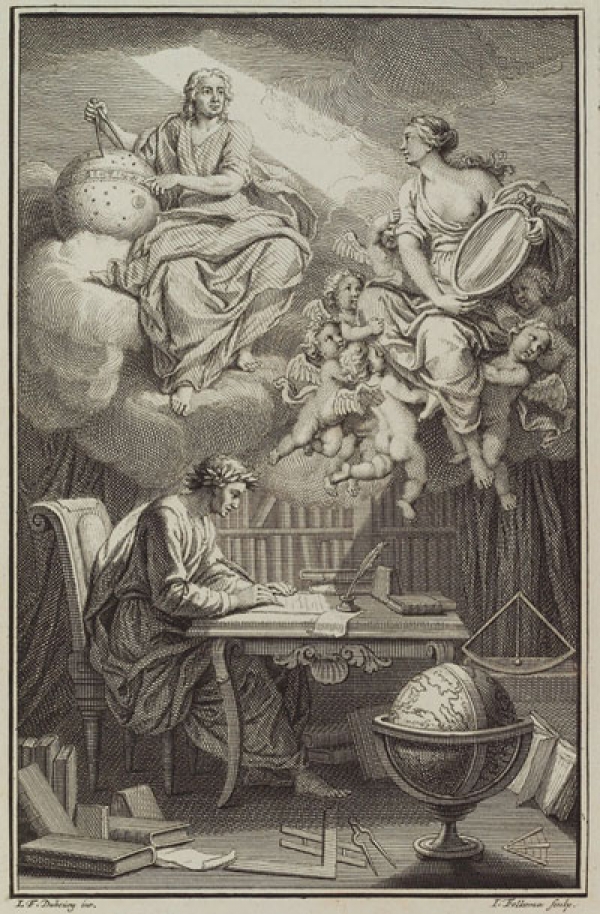

Voltaire to the Crown Prince of Prussia, 1 September 1736

Monseigneur, I would needs be insensible not to be infinitely touched by the letter with which Your Royal Highness has deigned to honour me. It has greatly flattered my sense of pride; but my love for mankind, which has always ruled my heart and which has also—dare I say it—formed my character, affords me a pleasure that is a thousand times purer when I realise that there exists in the world a prince who thinks like a man: a philosopher prince who will make man happier.

Allow me to tell you that there is not a being on earth who will not derive blessed benefits from the care that you take to cultivate sound philosophy in a soul born to command. Believe me, the only truly good kings have been those who, like you, began by acquiring knowledge, by getting to know mankind, by loving the truth and by detesting persecution and superstition. No prince who thinks like this can fail to create a golden age in his realm. Why do so few kings seek such advantages? You have sensed the reason, monseigneur, which is that almost all concern themselves more with royalty than with humanity—whilst you do precisely the contrary.

Be assured that, provided tumultuous affairs of state and human wickedness do not alter such a divine character, you will be adored by your peoples and treasured by the entire world. Philosophers worthy of the name will hasten to your domains and, just as famous artists flock to countries where their art is most appreciated, thinkers will come to gather around your throne …

The image is a detail from an engraving that purports to show Voltaire turning from his desk to converse with Frederick the Great (V did in later years accept the king's invitation to the Prussian royal court)

From Émilie to Maupertuis, August 1736

Can it be that I must still write to you at the Pole? … They say in the newspapers that you risked being eaten alive by mosquitoes: I’m very happy to learn they treated you with respect (possibly you owed this to the protection of Monsieur de Réamur), because it doesn’t look as though they valued you as highly as the Lapp women do …

We’ve become absolute natural philosophers. The companion of my solitude has written an ‘Introduction’ to his Elements of Newton, which he has addressed to me—I’m sending you the frontispiece. I trust you’ll find the verses worthy of the philosopher they celebrate, and of the poet who wrote them. If you’d been amongst us, we would have asked your advice. For a long time you’ve been wanting to make a natural philosopher out of the first of our poets, and you’ve succeeded: your advice has greatly influenced his determination to follow his bent towards scientific knowledge. As for me, you have some idea of what I’m able to perform in physics and mathematics. I benefit from a big advantage over the greatest philosophers, because I’ve been taught by you

While you’re changing the shape of the Earth, please leave Cirey just as it is and above all remember how much we love you here.

From Voltaire to Mademoiselle Quinault [of the Comédie Française], 24 August 1736

Ah, my God, delightful Thalia, you only needed to say and I couldn’t be happier—you want four lines of verse for the ending, and quick, quick, here they are.

No, they’re not here. You’ll find them at the end of my letter.

Far from perfect, I know, but still, you haven’t had to wait long for them; and then, delightful Thalia, you’re allowed to throw them in the fire …

Actually I have some hopes of this piece by Gresset. When with your artistry you spread a few comic touches over this cold Gresset, it will be greatly to his benefit. Given your touch, Gresset may succeed, but if he fails I give Gresset up completely and it will be all Gresset’s fault.

But when you do me the honour of writing to me, you never tell me we’ve played such and such a piece, or that our theatre is doing well. You tell me nothing about the republic of drama; do you consider me as a limb severed from the body?

While I’ve been writing to you, beautiful Thalia, and thinking that it’s you whom I address, I have to admit that the verses I just thought up at your request are not worth the devil. So here’s my second version:

MADAME DE PORKYBACK, to Pridefool

Oh, well said—in the end I’ll make him mine,

My president; I’ll bring him into line

For you. Come on, you pedant, get us wed:

Just get me married and we’ll shake the bed.

The above might be a bit limp but you be the judge; you’re the expert on what makes people laugh. I have no idea myself and don’t consider myself in the least funny …

Thalia, Thalia, if I were in Paris I’d work for you alone. You’d turn me into an amphibious animal, comic for six months of the year and tragic the other six. The trouble is, the world contains a devil called Newton who has discovered exactly how much the sun weighs and defined the colours of the rays that constitute light. This strange man has my head in a whirl; please write to me and bring me back to the muses.

I’m tenderly devoted to you for ever; don’t forget me …

I’m at your feet.

The painting by Nattier depicts Thalia, the muse of drama.

From Émilie to Count Algarotti [in London], May 1736

Do you have the translation of the Essay on Man? Apparently it’s a great success in Paris, translated by Prévost. The Abbé du Resnel is publishing his own translation in verse. All this is quite astonishing, when you think they burned [Voltaire’s] Philosophical Letters. The more I read Pope’s work, the more I like it. In the fourth Epistle, which you refused to read with me at Cirey, I found a line that I very much like: ‘An honest man’s the noblest work of God.’

Voltaire was shocked by these two lines: ‘All reason’s pleasure, all the joys of sense/lie in three words, health, peace, and competence.’ Here is his reply:

Pope, wise English poet, so exalted

For his Parnassian moral thought, decrees

That life’s sole blessings are: to work with ease,

Enjoy good health and rest. He’s to be faulted!

What? In treasures that the gods devise—

Man’s happiest gifts, sent from heaven above—

This sad Englishman does not count love?

Pity Pope; he’s neither gay nor wise.

Voltaire strives not to be wistful about the Académie Française

From Voltaire to Monsieur de la Chaussée, 2 May 1736

A week ago, monsieur, I searched out your residence in order to present Alzire [his latest play] to the man in France who best knows and cultivates the art of poetry, which so difficult to practise. I think just as you do, monsieur, about the art that all the world believes they know, and that so few know at all …

Of our exacting art, the only aim

Is to be even more precise than prose;

Thus for verse of genius we claim

That from the language of the gods it rose.

It must be said that you’re more worthy than anyone to justify this claim.

Today it was suggested to me that I might be elected to the Académie Française, but neither the circumstances in which I find myself, nor my health—nor my liberty, which I cherish above all—permit me to dare think of it. I replied that the place should be destined for you, and if your merits did not already secure you complete support I would be honoured to cede to you the few votes upon which I would have been able to rely [La Chaussée was subsequently elected to the French Academy].

The image is of the Institut de France, where the Académie Française meets. Voltaire was of course never elected to the Academy--too much of a firebrand.

From Émilie to Count Algarotti in London, 10 April 1736

I’ve sent you, monsieur, an in-folio manuscript of mine, much less to be valued than the four printed pages enclosed here [Voltaire’s dedication to Émilie of his play, Alzire]. I would never dream of letting you read the excessive praise lavished on me in those pages, if they didn’t also do such sound justice to you. The play itself is not yet in print, and anyway it would have made the package too large. I implore you to make sure that the Queen of England sees it—she reads French perfectly—and also to make sure that, if Alzire is translated and printed in England, the Dedication is likewise …

I beg you to send me your news, so that I’ll know where to write to you next, since I believe England is about to lose you … I’ve had one letter from our two Laplanders [Maupertuis and Clairaut] just as they boarded ship. Farewell, monsieur, and write to me. Voltaire is still in that big nasty city [Paris] enjoying his triumph [at the theatre]—they’re mad about him. I should be very annoyed if these high honours in any way lowered your conduct—you are both made to love Cirey, and Cirey is where you are loved.

Image: the river running through the hamlet of Cirey-sur-Blaise.

Shakespeare gets Voltaire into trouble!

From Voltaire to the Abbé Asselin, 4 November 1735

'I’m sending you the last scene of La Mort de César, which is a pretty faithful translation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Accordingly, the piece takes its place as a singular and quite interesting work in the republic of letters—which is precisely the point of view from which any journalist ought to have examined my tragedy. It offers a true idea of English taste. One doesn’t demonstrate the poetic genius of a nation by translating its poets into prose, but by imitating their taste and style in verse. A dissertation on this taste, so different from our own, is just what one would have expected from the Abbé Desfontaines [fierce critic of V. in the journal Observations des Écrits Modernes]. He knows English; he must have read Shakespeare; he had the opportunity to enlighten the public about all this. If, instead of crying down my piece with ‘What bad verses! What hard verses!’ he had cared to distinguish between the printer and myself, and had the critical wisdom to demonstrate the differences in taste between nations, he would have done a service to literature and would not have affronted me.

'I know poetry well enough (even though I don’t write it any more) to be confident that this tragedy, as it is now being printed in Holland, has the greatest poetic power of anything I’ve written. All its foreign readers—who by the way recognise in this piece the bold strokes that are used in Italy and London, and that long ago were used in Athens—do me greater justice than the Abbé Desfontaines and my enemies …

'Disputes between people of letters only serve to make fools laugh at the expense of people of intelligence, and to dishonour talents that should be held in respect … I hope the Abbé will come round to me with the friendship that I have a right to expect of him; my friendship will not be altered by our differences of opinion. You may communicate this letter to him.

'With much gratitude, I am attached to you for life.'

The show goes on

Writing opera our way--spent yesterday with Nicholas Gentile working on the finale for Act I of Émilie & Voltaire. Beautiful music, folks!

Émilie to the Duc de Richelieu, towards the end of 1735

What did Émilie confide to her friend and former lover, Richelieu, while he was staying with her and Voltaire at Cirey? She claims to be able to feel two deep emotions 'without the slightest self-reproach'. Nonetheless, I'm guessing the secret she shared with Richelieu is a somewhat guilty one.

'The conversation I’ve just had with you proves to me that man is not free. I should never have told you what I just confessed, but I had to have the relief of letting you know that I’ve always judged you fairly, and always recognised your value. Friendship in a heart like yours seems to me the best gift that heaven could bestow, and I could never console myself if I weren’t quite sure that, despite all your resolutions, you’re impelled to feel the same about me …

'I’ve given up everything to live with the only person who has ever filled my heart and my mind, but I would give up everything in the universe—except him—to share all the sweetness of friendship with you. These two emotions are not at all incompatible, since my heart is able to feel both at once, without the slightest self-reproach. The only true passion I’ve ever experienced is for what I have now, and it forms the charm and torment of my life, the good and the evil; but I’ve only ever felt true friendship for Madame de Richelieu and you …

'I’m happy to have seen you once more, even if I never see you again. I’m even happy about my indiscretion, because it revealed my heart to you—but I would be very unhappy if you don’t cherish my friendship and continue to give me proof of it …

'Farewell. There will be no perfect happiness for me in this world unless I can unite the pleasure of living in it with you, and that of loving the man to whom I have consecrated my life.'

Image: reflections in the Blaise at Cirey.

From Voltaire to Thiériot, 3 November 1735

We have the Marquis Algarotti with us [at Cirey], a young man who knows the language and morals of every country, who writes poetry like Ariosto, and knows his Locke and Newton. He reads us dialogues that he has written on the interesting parts of philosophy. Even I have undertaken my little course in metaphysics, because it behoves one to take account of the things in this world.

We’ve been reading stanzas of Jeanne la Pucelle [Voltaire’s risqué satire on Joan of Arc], or else one of my tragedies, or a chapter of The Century of Louis XIV. From there we’ve come back to Newton and Locke—not without champagne and excellent meals, because we’re very voluptuous philosophers; and if not, we’d be quite unworthy of you and your delightful Pollion.

So there’s a pretty exact account of my present life. And that’s why I'm not with you, my dear Thiériot. But be assured that life is the sweeter to me because I know how agreeable yours is to you. My happiness sends its very best regards to yours. Pay court to your charming benefactor on my behalf.

With our friend, drink health to me

In champagne whose vivacity

Sparkles as brightly as his mind;

Whilst here at our suppers refined

I drink with sublime Émilie

To you in ambrosia divine.

Image: Le Déjeuner d’Huitres, the Oyster Lunch. In this painting of the period one sees that champagne is drunk from coupe-shaped glasses. Note the airborne stopper after a servant cuts the pack-thread that held it to the bottle neck.

From Émilie to Count Algarotti, October 1735

It’s only fair, monsieur, that since I’ve just come searching for you in Paris, you should come and do the same for me. It would be very remiss of you to leave for the North Pole [Algarotti considered joining Maupertuis on his expedition] without making a visit to the Champagne, and my constant hope is that you’re incapable of doing me such a bad turn.

You’ll find my château still unfinished, but I hope you’ll be happy with your accommodation and especially with the pleasure it will give me to welcome you. Voltaire, who shares that pleasure, and who longs for your coming with the eagerness inspired by your friendship, is getting ready to sing your polar exploits in verse: you can tune your instruments together … My library is attractive enough. Voltaire’s is full of narratives, mine is all natural philosophy. I’m learning Italian for your visit, but the labourers in wood and weave make it very difficult. I’m busier than a state minister and a great deal less anxious; which is pretty much what one needs to be happy. Your company will greatly enhance the charms of my solitude. Please come, monsieur, and be assured of the extreme pleasure it will give me to welcome you.

The image shows the little river flowing through the village of Cirey-sur-Blaise.

From Émilie to the Duc de Richelieu, October 1735

I’d begun my letter intending to give you a long list of all the dangers you’d face on coming here [to Cirey]: being poorly housed, finding a hundred labourers in the place—in the end, being poorly received, if ‘poorly’ is what you feel when you’re urgently awaited with the tenderest friendship. But here I am mentioning it all again, and I imagine you’ll forgive me for the messy organisation of my colony. Voltaire says I’m just like Dido—or an ant …

You can well believe that if love hadn’t called me here, I’d have stayed in Paris. But amongst everyone I know, yours is the only company I wish for. Just being with your friend is enough to put me off other men; so you can judge what his love does to me. I’m sending you a letter [in verse] that he wrote to a Venetian, Count Algarotti—I couldn’t resist it. I might have sent it to you as President of the Academy of Sciences but I much prefer sending it to you as my intimate friend. Only a few days pass here without Voltaire writing a few little stanzas, not to mention whole narratives: I’m thinking of making up an Emiliana of all his poetry from Cirey; it would form a lovely collection. Come and see us, then—what are you doing under canvas [on the Rhineland campaign] in weather like this? I very much hope they’re not going to start sending you on new forays. They’ve sent the battle sergeants off; I’d much rather know the date when you leave yourself.

Voltaire on plagiarism: to the Marquis de Caumont, August 1735

So, monsieur, you’ve found in the letters of the late Madame d’Uxelles some particulars that you think might be useful to me? I beg you to believe that everything is of use to me; things that appear indifferent to others may serve to characterise the century that I’m examining [V. was writing The Century of Louis XIV]. For example, the decree in council that freed from prison all the unfortunate people detained for witchcraft is much more important to me than a battle—because battles are fought throughout history, whereas the mentality of peoples, their tastes, their stupidities, have not always been the same. An error erased, an art invented or perfected, seems to me far superior to the glory of massacres and destruction.

I share your view, monsieur, of The Life of Turenne [a famous French general]. I don’t despise the historian and I admire the hero. It’s true that the Life didn’t interest me but on the other hand it contains several quite well-written passages. The work shows us an intellect that is cold, but brought on by reading good authors. The only thing that annoys me is that he’s like those weak stomachs that bring things up in the same state as they swallowed them. I’ll allow him imitation, since he’s a foreigner, but not plagiarism. He’s a Scot who’s made a lot of money in France, but he shouldn’t be stealing from people.

As for the hero, I still say that he changed his religion either out of weakness or because it was in his interests. For I refuse to believe it was from conviction. Right up to his death he had mistresses who laughed at him; at the head of armies he betrayed his king; he told a state secret to a young woman; he lost five or six battles; given all that, I think he’s one of the greatest men we’ve ever had.

Image: Turenne, 1611-1675

Nicholas Gentile studies in Lucca with Fondazione Giacomo Puccini

Instead of a letter from Émilie or Voltaire this week, here's a news flash from Nicholas Gentile:

'I was lucky enough to receive a grant this year from Fine Music Australia to write a new opera.

'Well the next chapter has arrived! I’m thrilled to have been accepted on scholarship to travel to Lucca, Italy this July to study at the Puccini International Opera Composition Course.

'I’ll get to work intensively with some of the finest composers and opera conductors in the world on my new opera, Émilie & Voltaire.

For continuing updates on the development of the opera please consider becoming a patron here.'

From Émilie to Maupertuis, summer, 1735

I didn’t receive the first letter you speak of but that doesn’t make me any less guilty for not having replied earlier to your last, or rather for not having expected it. But I wasn’t fit to write to you: I spend my life with masons, carpenters, wool carders and sculptors in stone; I can’t think any more. I’m no better fitted to write to you today, but I can’t resist doing so. I have to say how much I miss you in my solitude, and how little I regret the rest of Paris. If I weren’t here, I’d wish to be at Mont-Valérien … But you, you’re about to take a leap from Mont-Valérien to the North Pole; you’re deserting the Great Bear for Ursa Minor. You only love me when you can’t see me.

Here [at Cirey] Voltaire admires you more than ever and deserves to be your friend. If I could get you both together, I’d consider myself much luckier than Queen Christina: she left her kingdom [Sweden] to run after so-called learned men, while it’s in my own realm that I shall gather the kind of men she would have sought much further away than Rome. You know it’s only the first concession that mars our sense of self-importance: since I’ve dared to write to you from amongst my stone masons, you can count on my being punctilious from now on. Don’t punish me for being shy at first: send me your news—and believe me, neither Madame de Lauraguais, nor Madame de Saint-Pierre, nor all the duchesses in the world could possibly feel a more tender friendship for you than Madame de Cirey.

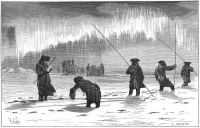

The image shows Maupertuis and his geometers/surveyors measuring an arc of meridian in the ice and snow of a river in Lapland: this is his expedition of 1736, to which Émilie refers, to prove Isaac Newton's theory that the Earth is relatively flatter at the poles.

From Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, 11 September 1735

These weekly letters, alternately by Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet, are chronological, otherwise I'd love to include here something beautiful by Voltaire on Notre-Dame, that beloved cathedral ravaged by fire just two days ago. However, as I recall, in his Temple du Goût, he preferred Baroque to Gothic architecture and considered Notre-Dame overdecorated. I'm sure he would have been devastated, however, by the catastrophe. It is heartening to hear President Macron's promise that the cathedral will be rebuilt.

I’m waiting for the delivery [of books and periodicals from Paris] without impatience, since I’m here with Émilie and The Century of Louis XIV, of which I’ve already done thirty years. There’s nothing in that century as admirable as she. She reads Virgil, Pope and algebra as one reads a novel. I can’t get over the ease with which she reads Pope’s essays ‘On Man’; it’s a work that sometimes presents problems for English readers.

If I weren’t by her side I’d be at yours, my dear friend. It’s ridiculous that we can be so happy while so far from each other. I’m truly delighted that Pollion la Popelinière thinks of me with some approval: ‘It’s to readers like him that I offer my writing.’ [A quote from the poet Boileau.] …

They say that Rameau’s opera would do well in the Indies. I think the profusion of his double crotchets might be putting off the Lully supporters. But in the end Rameau’s taste must become the dominant taste of our nation, as we become more knowledgeable over time. Ears are formed little by little. Two or three generations will alter the organs of a nation. Lully gave us a sense of hearing that we did not possess before. But men like Rameau will perfect it. You can tell me what you think about this, one hundred and fifty years from now.

My respectful compliments to your brothers and your sister. Adieu, I’ve a hundred letters to write. V.

Voltaire refers wittily here to Rameau’s opera-ballet Les Indes Galantes (pictured) which is still performed today—more than confirming his judgment of its longevity.

From Émilie to the Duc de Richelieu, September 1735

You’ll tell me I’m very difficult to deal with: I’m not happy with your letter. It’s not that it isn’t charming—it’s just too short; you don’t say anything about yourself. It’s true that you speak to me in a way that would make me even happier than I am, if that were possible. You must know how much I love you, since while I’m here in the midst of a felicity that fills both my heart and my soul, I still want to know what interests you, and share whatever happens to you. Your absence makes me feel I yet have something more to ask of the gods, and to be perfectly happy I should be able live between you and your friend: my heart is bold enough to desire it, and feels no shame over a sentiment that the tender friendship I feel for you will preserve within me, all my life.

You don’t tell me when you’ll come to see me, nor when you expect the campaign to be over, nor how tiresome it must be for you [Richelieu was brigadier-general in the Rhineland]. I’m quite happy to live cut off from the world, but I won’t be cut off from your friendship. Consider: if, in the boredom and inaction of this campaign you write such little letters to me, what will you do when you’re in Paris? You’ll forget me for six months! But at least I can be sure that you won’t fail to think of me with friendship and sensitivity.

More...

From Voltaire to Cideville, August 1735

My dear Cideville, the sublime Émilie has heard and approved your delightful work [a pastoral poem] and she considers that the poet who can put such tenderness in the mouths of his untutored lovers must have a very knowledgeable heart.

Monsieur Linant [a young tutor hired by Voltaire for Émilie’s son] and I are living in her château. It falls to her to teach Latin to the preceptor, who will then pass on to the son what he has just received from the mother. From her, both of us will learn how to think. We should take advantage of such a happy time … To be worthy of her, one must be universal. For my part, I am at present her stone mason.

My hand, by turn in days of yore,

Though rather shaky, raised with pleasure

The flute of love in lightest measure

Or else the trumpet sound of war …

These days I’ve roundels to be made:

Pilasters, capitals I hone

From our rough unfashioned stone,

Wielding the chisel’s tempered blade …

Apollo built the majesty

Of Ilion for kings, but here

I’m happier in this wondrous sphere

As stone mason to Émilie.

Apollo, banished from Olympian

Heaven, regrets the azure space.

What could I miss in this fair place?

I’m the one in bliss empyrean.

I pity you, my friend, for not being here. How unfortunate you are, having to judge trials! Why don’t you leave all that behind to come and pay court to Émilie? Adieu my friend, I have to go off and lay a few planks, then hear some charming things said, and gain more from her conversation than I would from any books.

I’ve started work on the century of Louis XIV. I’ve no idea what to call it. It’s not a history at all, it’s the portrait of an admirable century. Vale, ama, scribe [Farewell, love, write].

Nota that the divine Émilie sends you a thousand compliments, and she’ll write to you if the stone masons don’t prevent her from doing so.

From Émilie to the Duc de Richelieu, April 1735

I prefer romantic gossip to intellectual and so, since you give me free rein, I imagine my letters will end up in-folio. Yours came at just the right moment; I was going to write to you, to get in first, and let you know exactly what you’re like: you’re nice to people for a week, you flirt with the idea of being friends—but on my side, since I take friendship the most seriously of all things in my life, I worried about your silence and it hurt. I said to myself, one is supposed to love one’s friends with all their faults. Monsieur de Richelieu is flighty and fickle—I’ll have to love him as he is. At heart I was conscious that I was by no means satisfied with this bargain … I still grieved over renouncing the beautiful chimera of having you as a friend. You, whom everyone else thinks made for flirtation, you, whom I would never have taken it into my head to love—but whose friendship I can no longer do without …

I leave [for Cirey] in four days, so I’m writing to you from the muddle of my departure. My thoughts are heavy but my heart is awash with joy. I hope this decision will persuade Voltaire that I love him, which puts everything else out of my mind. All I can see before me is the supreme happiness of wiping away his fears and spending my life with him. You’re mistaken … there’s a great difference between jealousy and the fear of not being loved enough. You can defend yourself against the first as long as there’s no foundation for it, but you can’t help being pricked and wounded by the second. The first is a troublesome feeling, while the second is an insidious anxiety, and there are fewer weapons and remedies to counter it—except mine, which is to go and be happy at Cirey. Behold, in all earnestness, the metaphysics of love: now you see where excess of passion leads me.

Voltaire to Monsieur de Cideville, 16 April 1735

VOLTAIRE ON TRENDINESS IN THE ARTS AND SCIENCES--there shouldn't be any!

Truly my dear friend I haven’t thanked you enough for the lovely group of poems that you sent me. I’ve just reread it with fresh pleasure. How I love the naivety of the pictures you paint! How happy and rich your imagination is! And what gives such inexpressible charm to it all is that everything comes from the heart. You’re always inspired by either love or friendship …

I lead a dissipated life in Paris and all poetic ideas have fled. Business and duties crush my imagination. I should pay you a visit in Rouen to revive me. Verse is no longer fashionable in Paris. Everyone’s started playing geometers or physicists. People are toying with reason. Sentiment, imagination and the graceful arts are banished. Any man who’d lived under Louis XIV and happened upon today’s society would not recognise the French: he’d think the Germans had taken over the country. Everywhere you look, literature is in decline. It’s not that I mind natural philosophy being cultivated, but I wouldn’t like it to become so tyrannical as to exclude all the rest. In France, it’s simply a fashion that’s replaced preceding ones and will be superseded in its turn. But no art, no science, should ever be in fashion. They must all go hand in hand, and be cultivated all the time. I’ve no desire to pay homage to fashion; I want to be able to go from a physics experiment to an opera or a play, and never allow my taste to be blunted by study. Your taste, my dear Cideville, will always underpin mine, but we ought to see each other; I need to spend a few months with you, but destiny separates us just when everything ought to bring us together … Vale. V.

Émilie to Pierre-Robert Le Cornier de Cideville, 31 March 1735

VOLTAIRE NO LONGER WANTED BY POLICE! Here's the good news in a letter that Émilie wrote from Paris.

'I’m depriving your friend, monsieur, of the pleasure of letting you know himself about his return to Paris; I feel and I share your joy. I was extremely pleased to see him; this business of his has gone on for so long that I was almost afraid it would never be over—but at last he has been returned to us. It’s to be hoped that never again will he put us through such acute distress. I don’t know whether you’ve received a letter from me that I asked Monsieur de Formont to deliver. I still flatter myself that one day I’ll bring you together in the country home where I intend to spend some time. I’m sure you realise how urgently I desire to meet someone for whom I’ve developed an esteem that arises from friendship—and that I hope friendship will cement.'

Pierre-Robert Le Cornier de Cideville was a magistrate and writer who lived in Rouen (pictured); he was one of Voltaire’s closest friends and they kept in touch mainly by correspondence—often in verse.

![From Voltaire to Mademoiselle Quinault [of the Comédie Française], 24 August 1736](/media/k2/items/cache/a9ccd7cd1c4267a50c67ac0bd7180172_L.jpg)

![From Émilie to Count Algarotti [in London], May 1736](/media/k2/items/cache/1c6c813bb9d5494160041c1c4ee2fb70_L.jpg)