Welcome!

Cheryl Sawyer welcomes readers to her historical novels, blogs about discoveries in writing and research, and shares her experiences in the world of creative fiction. Cheryl has had a long career in book publishing, which she left in 2014, to write full-time. Her first historical novel was published by Random House in 1998 and her American debut in 2005 was acclaimed by Booklist as 'a grand and glorious delight'. More novels have been released in several languages by Penguin US, Bertelsmann, Mir Knigi, Via Magna, Domino, Reader's Digest and Endeavour Press UK. Cheryl Sawyer's work has been longlisted for awards by the Historical Novel Society and the American Library in Paris. She has recently completed an English Civil War trilogy with The Winter Prince, Farewell, Cavaliers and The King's Shadow. Peter James calls her work ‘historical fiction writing at its very best’.

Émilie du Châtelet 1738 - Episode 2

Nicholas Gentile and I have written an opera about Émilie and Voltaire and were invited to speak about it to Sydney's Queen's Club. Episode 1 of the speech shows Émilie as a girl being shown off by her fond father as a prodigy in mathematics and natural science. She also, with the approbation of her mother, excelled at playing the harpsichord.

'In a corner is a tall, lean young man who looks rather bemused by this precocious eight-year-old. Finally he steps forward when the company are speculating about the possibility of life on other planets. He gives Émilie a teasing smile and says, "Mademoiselle, could there be human beings on Mercury? Reflect: if they do live there, they’re twice as close to the sun as we are, so their brains must surely be fried. The sun is nine times bigger for them than it is for us—what does that do to their idea of the universe? Could anyone in that situation think like us at all?"

'She replies, "I have no opinion, monsieur; I’m here on earth. But if there are sentient creatures on Mercury, why should they be human? All we can guess is that they accord with the infinite diversity of nature."

'The silenced young man is Voltaire, a successful dramatist and poet, a keen philosopher and writer, and a huge asset in aristocratic society. He’s not an aristocrat himself, however. He was born François-Marie Arouet in Paris, near the law courts and Notre-Dame. He was educated at an excellent Jesuit college where he mixed with the sons of noblemen, dazzled his teachers with his intellect and wit, and wrote the school play at the end of each year. When he went into society he fitted in by making up a noble name for himself—"de Voltaire"—and forming liaisons with actresses or duchesses, and no one in between.'

Émilie du Châtelet 1738 – Episode 1

Émilie du Châtelet commissioned a drawing, 'The Apotheosis of Voltaire' from Charles Natoire in the mid-1700s. A good idea if you're a grand lady with privileges at Versailles and he's a condemned writer who's done more than one stretch in the Bastille prison? No. But Émilie was never one to bow to prejudice. Besides, Voltaire had honoured her extravagantly in the frontispiece to his Elements of Newton. I tried to share the 'Apotheosis' with you but it kept coming in upside down. So for once there's no image for this episode.

Nicholas Gentile and I have written an opera about Émilie and Voltaire and were invited to speak about it to Sydney's Queen's Club, at the invitation of Elizabeth Hemphill. I'd like to give you my speech in several episodes, starting here. They give you a picture of Émilie up to 1738, when our opera takes place.

'Nicholas and I are very grateful to be welcomed here today and we’re delighted to take you behind the scenes of our opera in progress, Émilie & Voltaire. The opera shows us one day in 1738, in the life of a real person, Émilie du Châtelet. Émilie’s is a woman’s story that every woman should know, so I’d like to begin by introducing her to you as a young girl. I invite you back in time, to 1714, when we find ourselves south of the Loire valley in France, at a country chateau called Preuilly.

'It’s evening and dusk is falling, and we’re in a salon that has something of the comfortable atmosphere of this one, though the chairs and sofas are not as well cushioned, and instead of looking out over Hyde Park we can see the little river Claise, gleaming through trees. The count and countess de Breteuil, whose country home this is, have gathered their guests together after a lovely summer day, to meet the Breteuils’ eight-year-old daughter, brought downstairs as a special treat to mingle with the company before supper.

'She walks around and answers questions politely, and at a kind lady’s prompting she plays a piece on the harpsichord. Gabrielle-Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil is a dark-haired, tallish, dark-eyed child, who is receiving a very thorough education. Her father is proud of her cleverness and he’s hired tutors for her in mathematics and natural philosophy (or science as we know it) alongside the usual Latin and literature. Her mother, however, insists on music and dancing lessons but disapproves of all the rest.

'Émilie’s father shamelessly shows off her talents, and to everyone’s astonishment she multiplies six-figure numbers together in her head and joins in discussions on the scientific authors of the day.

'In a corner is a tall, lean young man who looks rather bemused by this precocious eight-year-old. Finally he steps forward when the company are speculating about the possibility of life on other planets. He gives Émilie a teasing smile and says, "Mademoiselle, could there be human beings on Mercury? Reflect: if they do live there, they’re twice as close to the sun as we are, so their brains must surely be fried. The sun is nine times bigger for them than it is for us—what does that do to their idea of the universe? Could anyone in that situation think like us at all?"

Join me for the next episode and more insights into this extraordinary scientist of the Enlightenment.

From Facebook to facing books

I'm bowing out of Facebook and inviting readers to rediscover this website, so I'll be posting here more frequently from now on. My presence on social media and here was intended to bring people closer to my writing. And my principle project at the moment is the opera I've written with Nicholas Gentile, the first ever to be created specifically for the screen. So from now on the main topics on this blog will be Émilie du Chatelet, the film project Émilie & Voltaire, and my own writing, in that order.

After decades devoted to writing, I now recognise that Émilie & Voltaire brings to fruition something that I was searching for in 2011. Back then I conducted a secret interview with myself. Looking at it again today for the very first time, I realise that something I yearned for then has come into being, and it turns out not to be a novel but an opera libretto! Thanks to Nicholas and our film team, it will soon go out into the world. Here is my self-interrogation from 12 years ago, unedited.

Why do I write?

Because I’ve always liked to read stories and wanted to work that magic, of keeping someone enthralled when they’re curled up with a book. This is an old dream of mine. For the last two decades it’s been a drive, not very examined.

If it’s for a definable purpose, am I achieving that purpose?

Possibly there’s a purpose there, as I grow older, of telling something about the world of human beings, what they’ve done and what moves them. I don’t write from any psychology or sociology of history, though, and I don’t see any point in a catalogue of facts. Some readers looking for romance in my books find too many facts; others find the stories rich and dramatic. I don’t think I’ll ever know whether the purpose is being achieved. I should spend some time thinking about whether I have one, however.

Am I doing it more for me or for others?

The drive is deep so I guess it’s primarily for me. About me, though? Don’t think so.

Is it meant to have an effect on others’ lives?

I do want the reader to share my fascination with the events I touch on, so it’s partially an adventurous history lesson. And I want the characters to become part of the reader’s life for a while, to be believed in as complex creatures. Capable of surprising and disappointing. Capable of inspiration. The books are full of moral choices.

What sort of effect does it have now?

Varied. Some people cry when they read the books, usually in odd places. Fiona Henderson, my first publisher, cried when the Master died in La Créole. Nerrilee Weir, rights manager, dreamed of Jules from Rebel. The history grabs some people. Do my books make people think or change their view of the world? I’ve no idea.

What am I trying to express?

That we love. That as a species we keep love out of most of our dealings with others. That we can’t concentrate long enough on examining what we do. That our mistakes are monumental. That in our hearts we know what’s wrong.

Is my writing honest?

It uses story constructs hallowed by literary practice. If it were totally honest, perhaps it would be less planned, stranger. But maybe less powerful?

Does it reflect my deepest preoccupations?

Who knows? Deep preoccupations tend to stay down there, inside us, rarely recognised. So there’s no real answer to that question.

Is there any point in going on?

In the sense that writing is a discovery, yes.

If there is, what kind of writing do I want to do?

I want people to sit up and take notice of it. Why? I’m getting older and I still haven’t written a book that reaches out and moves a lot of people powerfully. I have a desire to do that. But until I find out why I have that desire, I’ll never write the book. I know it’s not basically a selfish impulse, but beyond that I’m not sure where it comes from or where it’s going.

Is writing my greatest talent, supposing I have any?

Yeah, for what it’s worth. Not much. Good enough perhaps if given free rein.

Would I achieve the (supposed) purpose better by another means?

No, not that I know of.

Is it a search for something?

Looks like it.

Nicholas Gentile, Cannes Short Film Festival

Nicholas, composer of our opera film Émilie & Voltaire, was recently nominated Best Composer in the Cannes Short Film Festival. He did not win the award but we are thrilled that he was nominated as one of four composers, from around the world, for this prestigious accolade from Cannes. And doubly excited for the future of the film, which will be co-produced in France.

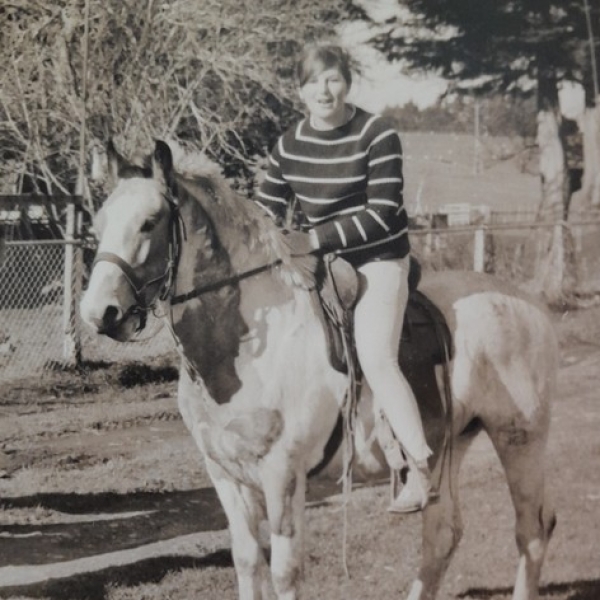

My first film review

The picture was taken in the country near Gisborne, New Zealand, in the sixties. I mean, it’s so tell-tale: when else would a teenager on holiday sweep her hair up and choose white jeans to ride a horse? This was at the end of my last year at school, a period in which I kept the one and only diary of my life, which lasted until November 1966.

Rediscovering the diary, I came across what I realise is my first film review. It is interesting (at least to me, now I’m writing screenplays) to note that it isn’t a fan rave about Peter O’Toole (though I adored him, particularly for his Henry II opposite Richard Burton’s Becket) but a writer’s assessment of how the film is put together. Here it is verbatim, with all its sins upon its head.

‘Today I went with Sue Flanigan to Lord Jim. Starring Peter O’Toole. In this I missed a real speech, too many incoherent half-sentences. True, Jim was not talkative in the book. Too coiled up inside. The real flow of the narrative, picturesque, arresting, penetrating, came from Marlow in the book. In the film a Jack Hawkins Marlow gave a few conventional, regretful remarks and left Jim to his tortured silence. Unfortunate, the film desperately needed Marlow. Even a direct clash with hostile forces and a dramatic rescue soon after Jim’s arrival failed to speed up the action before Jim’s seizure of power in Patusam. Either the film script needed a Marlow or the plot must be thickened. Richard Brooks did neither. He was happy to tamper by removing but not by addition. He retained some hideously difficult scenes (to act, I mean) and shifted characters so that the scene could be filled with more than just a man and his thoughts in many parts. Brooks retained quite well the theme of Tuan Jim. It was simple enough anyhow. Simplicity was perhaps the difficulty. After all, Conrad originally intended it to be a short story, didn’t he? It widened into a deeper personal narrative and almost a dissertation on men and the fantastic complications which their sense of ‘honour’ can achieve in their lives. Much of it, let’s face it, is padding. A seaman’s yarn, with deep and engrossing stories all thrown in, almost as asides. Jim’s love of the girl. Dain Waris. Stein. Although Stein and the villain are necessary figures. The book rambles unashamedly but the reader has the chance to glance back and pick up the thread of the theme, reread the final conversations with the villain of the piece (excuse the music-hall bit but what was the man’s name—Brown?). The book triumphantly emerges as a whole.

‘The film was slow. It had to be because there was no Marlow to weave a texture of words over the bare thread of the action. The padding, the relationships between Jim and the others proved unattainable in a film if used in Conrad’s original form. There were relationships not of action but of feeling. They were irrepressible, particularly by Jim.

‘Perhaps Peter O’Toole did play Jim as a “neurotic bore”. If so it was not his fault. Or Joseph Conrad’s. The whole idea should have been scrapped in the first place. Lord Jim is simply not a film. It’s not spectacular enough to pass off as a "great epic" and earn millions by catering to vulgarity. It needs sensitivity and a sort of 6-dimensional approach, a panorama of emotion and exposition, I don’t know, and I suppose you couldn’t have Marlow droning away – genius or a new medium to put it anywhere except on the pages of Conrad’s book. Therefore it’s not an "art" film either. It’s an irritating middling.’

Dear reader, was I dreaming already of Émilie & Voltaire in my desire for six filmic dimensions? It could be said our streamed cinematic opera will provide them. Emotion: Nicholas Gentile's divine music, the jealous lovers, the passionate lyrics. Exposition: the authentic setting of Cirey in France, a true historic discovery, a woman’s groundbreaking contribution to science.

A night in Okarito: in memoriam Keri Hulme

A night in Okarito, March 1988. There are few chairs in the big, circular living room that Keri Hulme built herself, so I am sitting on cushions with Bert Hingley and Robin Morrison, our backs against the book-lined wall. Keri is convivial and funny, whilst lamenting the caution of the helicopter pilot she hired to fly us over the Franz Josef glacier during the day. Fog and vicious winds have annulled this expensive treat but we are only too happy to enjoy her generosity in the warm space that I first glimpsed in The Bone People.

We are drinking South Island wine that we brought with us: Robin has just completed a commission for Hodder & Stoughton, photographing new vineyards for Michael Cooper’s latest Wines and Vineyards of New Zealand, and has kindly driven us down the west coast to this hamlet. Among them, Okarito’s eleven inhabitants manage to run a single motel, and a post office that provided a vital fax line between Keri and myself during the editing of The Bone People, four years ago. Keri is allergic to still wine, so thank the gods we have it, otherwise we’d be taking unfair advantage of her magnificent cellar of French champagne and Scotch whiskey. Robin, always versatile with the good things of life, has his own Tullamore Dew to hand.

Fluent and expansive in her writing, Keri is vivid and direct in speech: she relishes watching me cringe over her description of tomorrow’s breakfast—whitebait thrown live into the pan. Her range of reading is equally voracious. There is a scene in her novel where the boy Simon arranges shells on a beach—it has always made me wonder whether Keri has read Dorothy Dunnett, whose gloriously overwritten historical novels I loved as a teenager. Now I can ask. She sparkles at the reference and confesses to having all Dunnett’s Lymond chronicles.

As the others continue talking in this unique place, I’m seeing Simon on the beach and I’m even more aware of the richness of Keri’s work. One of the great novels of the twentieth century, The Bone People now speaks to millions of people, but the impulses behind it are impossible to categorise. Besides, in the literary world it’s fashionable to analyse the form and style of prize-winning novels: it’s not fashionable to believe they have a purpose. However, in this instant I know for sure that Keri is more about substance than style. I interrupt the others to ask, ‘You wrote your book so people won’t hit their kids, didn’t you?’ She says, ‘Yes.’

The Bone People was a force in itself before I read it, and many publishing stories can be told about it. Not least David Elworthy’s: as publisher at Collins, he loved the manuscript, and asked Keri if she would consider talking about it, then never heard from her again. David is a wonderful friend and was philosophical about Hodders’ eventually publishing it. Others who had reason to regret The Bone People moving out of their hands were Bob Ross and Helen Benton, who as Tandem sold the Spiral edition all over the country. Their immense energy and commitment drove it into bookshops and early success.

Keri’s novel was riding on a groundswell of recognition when Bert bought it in Palmerston North as a present to me. He read it in one sitting and decided Hodder & Stoughton should bring out an edition if at all possible. He went to Wellington to meet with the Spiral team and was impressed by them all, particularly Erihapeti Ramsden. He had great respect for what Spiral had done, as they were not essentially publishers and only brought the book out because they believed in it totally. On Keri’s approval they agreed to a Hodders edition, with their logo included on the spine. When it won the Booker Prize in London in 1985, they were there with waiata to receive it on her behalf.

Keri did not like to travel and was shy in public but she did attend a celebration at Hodders’ premises in Auckland. Bert asked Michael King to speak and Keri was moved by Michael’s gift of a Ngai Tahu pounamu adze that had been in his keeping some years and that he believed should go ‘home’ to her. It was an inspired gesture of respect.

I first worked freelance for Hodders in London, where Bert was with Heinemann Educational Books. I felt honoured a decade later to edit their edition of The Bone People. It is a powerful, structurally undisciplined novel of astonishing originality—in my view, asking Keri to alter it substantially would be as ridiculous as suggesting a revision of Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. I edited for clarity, ensuring that each passage said what Keri had meant to say. This meant a hilarious to-and-fro by fax from Auckland to Okarito as I checked whether certain puns were her neologisms or slips by the first typesetter.

Also rather hilariously, I got silent flak from CK Stead when some time later I applied for the publisher’s position at Auckland University Press. His question from the admission panel was about The Bone People. He asked me, if for the sake of argument the book had been accepted by AUP as a new manuscript, would I have subjected it to a more interventionist edit? I said no, and I could see from his eyes that I’d given the wrong answer as an applicant. But it was the right answer about a work of genius! We had a friendly dinner with Karl a couple of years later in Sydney and he confirmed that AUP was doing beautifully without me …

Back in Okarito, the night at Keri’s goes on into the small hours as we move to her next-door neighbours’ for music and a high-kicking dance taught to us by Keri, causing an ache in the calf muscles that persists next morning when I walk along the grey, windy beach. It is one of our last nights in New Zealand before our family migrates to Australia. The whole occasion happens at Keri’s insistence—hearing that Bert was transferring as publishing director to Hodder & Stoughton, Sydney, she was adamant that he could not leave the country before visiting her in Okarito. He accepted without question.

I’ll always be grateful for that revelatory, raw, exciting and magical experience. I honour Keri’s honesty, her courageous spirit, her clear-eyed record of what humans are capable of doing to one another, and her love of country and its people.

I am whakama about this, Keri, as I offer you my true farewell.

Voltaire's last letter for 2021

In my extracts from the letters of Voltaire and Madame du Châtelet, I've now brought these two amazing people to 1738, when they are living together at Cirey, Émilie's country mansion in the Champagne. They are writing separate works of their own, but collaborating now and then in scientific experiments that Voltaire carries out under less stringent conditions than Émilie would like.

In fact this situation led to Émilie's first attempt to be published as a physicist: when Voltaire based an essay on Fire partly on their experiments, she found her ideas outstripping his and decided to enter the French Academy of Sciences competition with an essay of her own. But she did not share this secret with her lover for many months. What happened when the results of the competition came in? The opera I've written with composer Nicholas Gentile explores this very event, which occurs on a single climactic day in 1738.

The blog is now up to date with the opera and I must think about what I'll pursue on these pages in 2022. I would like next year to see completion of the music and preparation for the film of Émilie & Voltaire, and I will keep you tuned into our progress on this page. Best of all, 2022 bids fair to be the year in which we find the co-producers for the film. To our knowledge, Émilie & Voltaire is the first opera ever written specifically for the screen. Of course we are not forgetting that it's also beautifully suited to the stage, so watch this space for notice of concerts and performances.

So here is Voltaire's last letter for 2021. He charmingly couples thinkers of the past with those of his own day as he writes to one of the priests who taught him at college in his teens.

Despite my dealings with Newton-Maupertuis and Descartes-Mairan, my heart has not ceased to cherish Quintilian-d’Olivet or regard him as forever my teacher and friend … I spend my days, dear Abbé, with a lady who manages three hundred workers, who understands Newton, Virgil and Tasso, and who thinks nothing of playing cards as well. There is the example I aim to follow, though I’m far behind her. I tell you, my dear master, that I see no reason why the study of physics should crush the flowers of poetry. Is Truth so dire that it deserves no ornament? The art of thinking and speaking eloquently, of feeling keenly and expressing oneself in a like manner—can this be inimical to philosophy? No, because without it we’d be thinking like barbarians …

I know there are people who are astonished, and who even do me the honour of hating me, because having begun with poetry I then moved on to history and ended up with philosophy [including the sciences]. But, I ask you, what was I doing at college when you had the goodness to form my mind? Whom did you get me and my schoolmates to learn by heart? Poets, historians and philosophers. How ridiculous if the world is afraid to demand of us just what was demanded of us at college, or to expect the same things of our intellect as we practised in our youth.

I know only too well—and of late I feel this even more—that man’s mind is very hidebound; but that’s all the more reason to try to extend the frontiers of its little realm, and fight against the natural laziness and ignorance we were born with. It’s impossible for me to conceive the plot of a tragedy or carry out physics experiments in a single day, sed omnia tempus habent [but all things have their time]. Thus, when I’ve spent three months amongst the thorns of mathematics, I’m happy to be back amongst the flowers.

Émilie to Maupertuis 11 January 1738

I'm thrilled by the beautiful new music for our opera, Émilie and Voltaire, that has been coming to me from Nicholas Gentile. The latest sounded like a wonderful manifesto for Émilie as scientist, so here is the new aria I added to the libretto:

'This haven of mine

Brings me the rare pleasures of peace and liberty

My chateau is a shrine

Both to science and love.

This landscape divine

Shows me the way into a lucid clarity.

Ideas in my mind

Soar to the sky above.

'My lover can say

His knowledge too grows here

In the gentle countryside

And so we work in the clear light of Cirey.

Ah!

'Yes, the world will rejoice

When I am known

Through words of my own

And everyone will hear my voice.'

I look forward to letting you hear that voice when we're ready to release a demo of the aria.

Meanwhile here is Émilie in real life, writing to Maupertuis in January 1738.

'I would have written to you much earlier, monsieur, if I’d thought you were unhappy, because however philosophical we happen to be, and however superior we feel to those who are incapable of admiring us, it’s hard to see mistaken ideas triumph, and to meet nothing but opposition as a result of the work that we’ve undertaken and accomplished. The fact is that no one in France wants Monsieur Newton to be right. Nonetheless it seems to me that some part of his glory has been reflected back onto your country as a result of your efforts. To the extent that I wouldn’t be surprised to see the Parlement pass a decree against Monsieur Newton’s ideas, and against you in particular.

'I believe it’s to these circumstances that we can attribute the refusal to allow the release of [Voltaire’s] Elements of Newton in France. We are heretics in science. I admire my own daring when I say "we" but even the kitchen boys in the army say, "We’ve beaten the enemy!"

'I sometimes rejoice in the opposition you have to face because it will afford me the pleasure of seeing you here: I beg you to prefer my place over any other retreat, including the Mont Valérien. I flatter myself that the life we lead here will please you. Certainly, the only thing that’s lacking here is your presence.'

Voltaire from Cirey, 20 June 1738

Those who claim that poetry, like love, is the province of youth, are quite right. And one can prolong one’s youth a little too far … Mind, I don’t maintain that no one should write verse after the age of thirty: on the contrary, that’s normally the only age at which one’s poetry is any good. Racine was around thirty when he wrote Andromaque, Corneille wrote The Cid at thirty-five, Virgil began the Aeneid at forty. I began the Henriade at twenty; I’d have done better to wait until I was thirty-five. But if I were to write an epic poem at sixty, I can tell you it would be pitiful. You can be pope or emperor in extreme old age but you can’t be a poet …

Therefore, having reached forty-three, I’m giving up poetry. Life is too short, and the spirit of man is endowed with too much thirst for serious inquiry to waste time searching for assonance and rhyme. Virgil and La Fontaine both lamented that they knew no physics:

When will the nine sisters, far from royal courts and towns,

Take me thoroughly in hand, and teach me how the skies

Revolve in diverse movements unfamiliar to our eyes—

The names and properties of all those wandering lights?

What Virgil and La Fontaine mourned, I now make my study. I divide my time between learning about nature and studying history. Twenty-five years are quite long enough to devote to poetry; and to all those who’ve dedicated their springtime to that difficult and delightful art, I recommend that they consecrate the autumn and the winter of their lives to simpler things, which are no less seductive, and which it’s shameful not to know.

Emilie to Algarotti, January 1738

This is exciting: I've brought Voltaire and Émilie's correspondence to 1738, the year when our opera is set! Here Émilie is writing to physicist and poet Francesco Algarotti: the frontispiece of his book Newtonianism for Ladies shows them together.

You’re no doubt aware that Monsieur de Maupertuis is back: the accuracy and the beauty of his calculations surpass everything that he himself could have hoped for … The reward for so much accuracy and endeavour is persecution. The old Academy has risen up against him and Monsieur de Cassini and the Jesuits—who as you know reckoned the earth to be flatter in China—are united: they have persuaded the idiots around them that Monsieur de Maupertuis has no idea what he’s talking about, and half or perhaps three-quarters of Paris believe them.

He’s had to struggle against a thousand difficulties to get his account of the voyage and his calculations printed and I’m not sure that he’ll manage it. The payments for his royal commission [to travel beyond the Arctic circle and measure an arc of meridian to prove that the Earth is flatter at the poles] are so paltry that Monsieur de Maupertuis has refused to accept his and has shared it amongst his companions. In short, no one in France wants Monsieur Newton to be proved right.

Nonetheless, by his calculations, Monsieur de Maupertuis has positively concluded and geometrically proven that the Earth is as flat as its inhabitants.

I'm also able to let you hear Julie Lea Goodwin perform an aria from the opera at the Qudos Bank Arena in June: here

Voltaire on poetic ideas

My translations of selected excerpts from Voltaire’s and Émilie du Châtelet’s letters began with the year in which they met (1733) and are just about to reach 1738, the year in which our opera Émilie & Voltaire is set—the award-winning composer is Nicholas Gentile, recently winner of the Mary Lopez Scholarship (above right). This letter from Voltaire to Frederick, Crown Prince of Prussia, was written on 20 December 1737. I’m giving you V’s impromptu verse in French so you can see how amusing and challenging it is, especially to one who feels compelled to attempt it in iambic pentameter …

You have commanded me, monseigneur, to present you with some rules by which to distinguish French words that belong to prose from those consecrated to poetry. We might wish that such rules should exist, but we scarcely have them for our own language. It is my impression that languages evolve like laws: little by little, new needs that come to our notice give birth to laws which appear to contradict one another. It seems that man has a bent for behaving and speaking at random. Nonetheless, to bring some order to the subject, I shall define poetic ideas, devices and words.

A poetic idea, as Your Royal Highness knows, is a colourful image substituted for a naturalistic idea of the thing about which one is speaking. For example, I would say in prose: ‘There exists in our world a young, virtuous and talented prince, who hates envy and fanaticism.’ I would say in poetry:

O Minerve! ô divine Astrée!

Par vous sa jeunesse inspirée

Suivit les arts et les vertus.

L’Envie au coeur faux, à l’oeil louche,

Et le Fanatisme farouche

Sous ses pieds tombent abattus.

Oh Minerva! Oh divine Astraea!

How you inspired his young idealism,

And of the arts and virtues made his crown.

False-hearted envy, the betrayer

Of truth, and pitiless fanaticism—

Both these beneath his feet are trodden down.

Nicholas Gentile and Émilie & Voltaire on Sky News

Wondering how Émilie & Voltaire is progressing towards our dream: a French-Australian co-production of the feature film? Nicholas Gentile explains on Sky News in May!

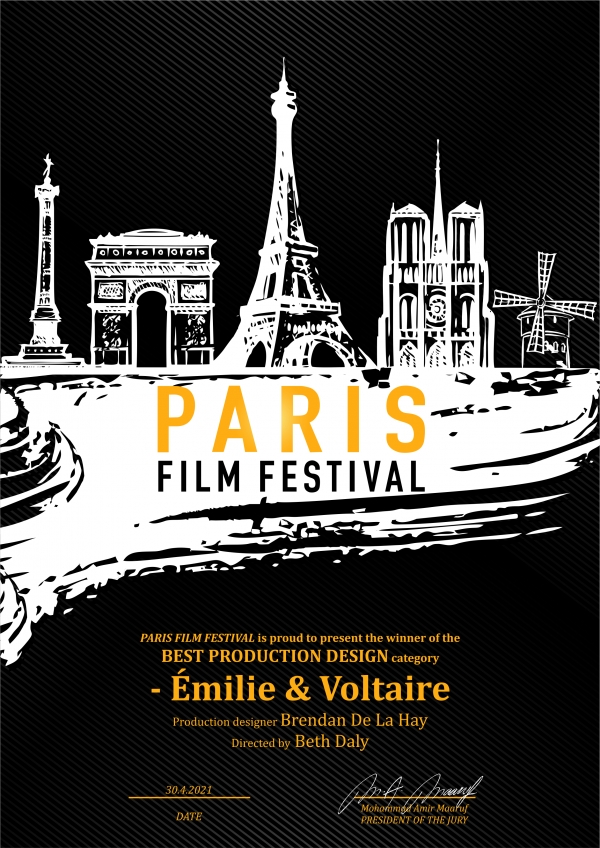

Paris Film Festival award for Émilie & Voltaire!

Yes, winner of the category Best Production Design. Due to pandemic restrictions the Paris Film Festival cannot do live screenings in the Le Bardy theatre or network events in cafes in central Paris but they will create 'Festival TV' on their website to show the winning films. In an earlier blog on the making of the Proof of Concept film in November 2020 I celebrated Brendan de la Hay's work on the set--congratulations, Brendan, for this recognition. And huge kudos to the whole team (see my earlier blogs).

This is an important step along the way to the full feature film of Émilie & Voltaire. It's been an exciting journey so far. Back in March 2018 when I sent composer Nicholas Gentile the first act of the opera, he asked for the libretto to be in French as well as English, and to exist not just as a staged opera but as a film, which would eventually be distributed through streaming services to offer accessible opera to millions for a fraction of the price of a regular opera ticket.

We realised not long ago that to our knowledge Émilie & Voltaire is the first opera ever to have been written specifically for the screen. The proof of concept film that just won the Paris Film Festival award is screening at the Puccini Opera Festival in Lucca on 15 May, with Italian subtitles, of course, provided by poet Paolo Totaro.

With the full screenplay well under development, we are aiming for an Australian/French co-production with exterior shooting on location at Cirey, the château in the Champagne region which Émilie and Voltaire made into one of the birthplaces of the Enlightenment, and from which Émilie made her mark as a physicist.

Émilie to Maupertuis, 11 December 1737

Everyone’s telling me about your success and the way you lectured the Academy and the public [Maupertuis gave his public address to the Royal Academy of Sciences on 13 November] … But however sweet it is to me to hear the world sing your praises, and to pay you the tribute of admiration that I have offered you ever since we met, I can tell you that it would be even sweeter to hear of your success from your own lips. You should send your manuscript [The Shape of the Earth] to Cirey, where arguably we deserve to read it, and it’s hard having to wait until it’s printed. Monsieur de Voltaire, who loves and esteems you more than anyone, has asked me to beg you to do so …

In the hope of tempting you to Cirey, we can tell you that you’ll find here a rather handsome physics collection, telescopes … hills, from the tops of which you can appreciate a vast horizon, and a theatre, with troupes for tragedy and comedy. We would act Alzire or The Prodigal Son for you, because at Cirey we only put on plays that have been written here—that’s one of the principles of the troupe.

But it’s quite obvious we won’t see you at all, so do think of me on your Mount Tabor [Maupertuis lived on the outskirts of Paris at Mont Valérien]; remember the first time I arrived there; give my compliments to the Superior, whom I’d be charmed to meet again; drink to my health in the refectory and, wherever you may be, always remember that there is not a place on earth, or anywhere else for that matter, where you could possibly be more loved and wanted than at Cirey.

Voltaire to the Abbé Moussinot, November 1737

The Abbé (a clergyman) was Voltaire’s business manager in Paris; he and his brother took care of V’s enterprises (amongst these being a paper factory), publishing his writing (through booksellers), lending money to aristocrats (including friends like the Duc de Richelieu) and sending purchases to Cirey. There are very long lists in this letter: I give just a few items from each.

Your patience, my dear Abbé, is about to be sorely tried; I tremble lest it collapse under the strain. I count entirely on your friendship. Temporal affairs, spiritual affairs—these are the subjects of the long chat I’m about to begin with you.

Monsieur de Lezeau owes me three years’ interest—you need to press him for it without being too harsh … Villars and d’Auneuil owe me for two years; you must politely and properly remind these gentlemen of their duties to their creditors. Please settle with Monsieur de Richelieu also … although I have great objections to what he proposes, I much prefer agreement to making an objection.

Prault must hand over fifty francs to your brother. I insist: it’s a bagatelle compared with what he’s made from my sales [of The Prodigal Son, a hit play] … Your brother will then berate Prault on my behalf—every time he sends me books there are delays that torment my patience; nothing ever arrives on the due date. Your brother will then ask him, or someone else, for Mariotte’s On the Nature of Air and On Heat and Cold … Boyle, De ratione inter ignem et flammam …

Other commissions. Two reams of writing paper and the same of letter paper (from Holland); twelve sticks of Spanish spirits-of-wine sealing wax, a Copernican sphere … two globes on stands … two barometers—the longest are the best … When purchasing, my friend, please choose the fine and the good at some expense, rather than the mediocre for less.

What follows is for the physical man, who has poor digestion, who greatly needs (so he’s told) to take exercise and has other social needs besides. Consequently, please buy me a good shotgun, a nice-looking game bag with appurtenances … diamond shoe-buckles, further diamond buckles for garters … two enormous pots of orange-flower pomade … finally three pairs of well-padded slippers; and then I can’t remember anything more.

All this will make one big package, or two if necessary, or three if you must … Send it all via Joinville, not to my address, because I’m in England (I beg you to remember), but to Madame Champbonin’s [a neighbour near Cirey].

All this costs money, you’ll tell me; and where to find it? Wherever you like, dear Abbé—one does discreetly own shares. One must never neglect pleasure, because life is short. I’ll be all yours for this short life.

Émilie to Maupertuis, September 1737

How Émilie would have loved texting! Distances can be so frustrating ...

So at last, monsieur, here you are back from the other world (because we can’t count Lapland as belonging to this one). I would have let you know how delighted I am before now, if I’d thought you would have time to read my letter. You have so many people asking you questions that I shan’t ask you a single one. My wish is that you’ve returned from your icicles in good health and with a little friendship for me …

I imagine you’re stuck in Paris on holiday. Which means we’ll be stuck here for ten years before we can see you again. Joking apart, if you were ready to snatch some time away from the gaping crowds and come to see a man who admires and loves you much more than they do, I’m offering to send a carriage for two, whenever you like, for you and Monsieur Clairault—because, despite his strictures [Clairault was a mathematical mentor for Émilie], I’d be enchanted to see him. I think if I want my compliments to be well received I should send them through you, so I’m asking you to say lots of nice things to him from me. While you, monsieur, know how genuine my friendship is for you, so I believe you’ll be happy for me to assure you of it once again, without the compliments.

The image is of Julie Lea Goodwin as Émilie and John Longmuir as Maupertuis during a break in the shooting of the concept film, Émilie & Voltaire.

Voltaire to the Crown Prince of Prussia, October 1737

In this first month of a new year I bring you the forty-first letter I’ve translated from the correspondence of Émilie du Châtelet and François-Marie de Voltaire. With these letters I aim to give you a picture of their lives together at Cirey, up until the amazing event in 1738 that sparks the action of the opera Émilie & Voltaire.

Monseigneur, I find it very hard that Cirey should be so far from the throne in Remusberg. The blessings and the commands that you send me take a long time to arrive. On 10 October I received a letter sent on 16 August, full of verses and excellent morality, and fine metaphysics, and grand sentiments, along with a goodness that enchants my heart. Ah, monseigneur—why are you a prince? Why couldn’t you be a man like any other, just for a year or so? Then we would have the happiness of seeing you—the only pleasure missing from my life since you deigned to write to me …

Our little paradise at Cirey sends its very humble respects to your empyrean heights, and the goddess Émilie bows before the god Frédéric. And so after a thousand detours I’ve received your beautiful letter, the ode, and the third folio of the metaphysics of [Christian] Wolff. Here is another instance of those benefits that other kings—those poor fellows who are only kings—are incapable of bestowing.

I must tell you that this piece of metaphysics—rather long, a little too full of commonplaces, but otherwise admirable, well put together and often most profound—I must tell you, monseigneur, that I understand not one iota of that simple being named Wolff. In an instant he transports me into an atmosphere in which I cannot breathe, onto ground where I cannot set foot, amongst people whose language I cannot understand. If I dared to think that I did understand it, I believe I might be brave enough to argue with Monsieur Wolff—with the greatest respect, of course …

The photo is of Rheinsberg Castle, then known in France as the Remusberg.

A strategic tenor

As an opera writer and reviewer I ask tenor John Longmuir, who plays Maupertuis in the concept film of Émilie & Voltaire, which classic opera role attracts him the most. He names Don Ottavio from Mozart's Don Giovanni and I am surprised, having always seen Ottavio as somewhat ineffectual. I also wonder whether Ottavio was really in love with his wronged fiancée. John coolly considers he 'probably' was, and gives me another vision of him, as strategist. Rather than wasting energy on futile challenges, Ottavio plans revenge on Don Giovanni by gathering aristocratic allies.

I suddenly see links between John's concept of Ottavio and the way he plays Maupertuis. Maupertuis is a man of action, but his tactics are calculating: when he sets out to woo Émilie to Paris he is full of praise for her scientific knowledge, not his own. His conversation is seductive and he implies that he's a more than worthy rival for Voltaire but he never actually says that he loves Émilie. Does he? Even I, having written his lines, cannot quite be sure, even as he delivers them.

Only once, when after a long pause he sings just her name, and pauses again, do I think that probably ...

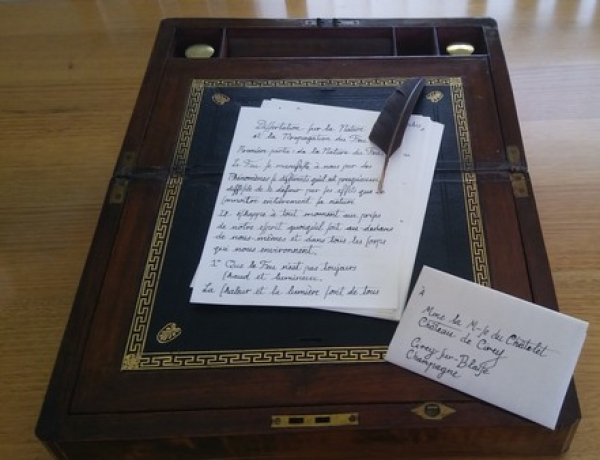

From my filming diary: dressing the set

Brendan de la Hay was a wizard at enhancing the beauty of the set and it was his idea to fill the parterre pond with fresh rose petals. Brittanie Shipway, second AD, was keen to add crimson petals but it took a bit of persuasion. She, Brendan and I had to fish them all out of the pool again when we packed up on the third day!

'Among the props I brought for the desk in the library are ... four beautifully bound books; several sheets of paper with maths, French writing & geometrical diagrams, plus a blank sheet rolled up with red ribbon ... three "quills"; Émilie's essay; the letter from Maupertuis ...'

'I just got called away to create yet another scribbled-on piece of paper for Émilie ... It will be fascinating to see how all these things get handled and used. Ease and clarity of music take priority.'

'I thought the desk was a bit overloaded, the way Brendan wanted it, but it seems to work in the shot.'

'Rob is just singing "Magique scène" to himself in the corridor.'

Concept filming 1.01--the setting

Just received this image of Beth Daly and myself watching shots come together in the garden of Lindesay House, Sydney. Here are some of my notes about the setting of the concept film.

‘From the terrace one looks down across a formal garden that ends in a curve of foliage, beyond which one sees the harbour.’

‘There is an enormous, gorgeous plane tree dominating the parking circle … The tiles in the hallway here are black and white—so are the tiles (larger) in the sale d’entrée at Cirey! Also of course there are the beautiful plane trees on the bank of the Blaise at Cirey.’

‘The actors and director are completely immersed in the three-fold story. I love their interpretations, and it’s fascinating to get intense snatches of what will later be a seamless drama.’

‘Is there a spirit that infuses a film while everyone’s working? It occurs to me that this House does provide something by just being itself. A little consistent world in which this is all happening.’

The stills photographer is Reswin Bahas.

Émilie & Voltaire concept filming 1.01: calling the shots

The shot list was put together by cinematographer Aravind Shanavaz and executive producer Nicholas Gentile, who is the composer of the opera. In the three-day shoot he literally conducted every take. The process and the vocab were all new to me: thought you might like to hear some of it at random from my diary.

‘That was very fresh, wasn’t it?’

‘She walks slower, slower, then again here … Boom … Boom .. Turn around.

‘Are we good, are we good? One more for safety.

‘She’ll start singing, that’s fine. Just go for pretty, go for pretty, then you’ve got all of her line to get there.’

‘Rob, when you do this, can you find a reason to do eyes back in this direction?’

‘How many takes for this do we have time for after lunch?’ Firm answer from Demi Louise, producer: ‘None.'

The unseen demands of playing Voltaire

Robert McDougall as Voltaire, waiting to be ‘alone’ in the garden with Émilie—but in reality he’ll be surrounded by at least five of the film crew! How do actors do it?

From my filming diary: ‘The idea of these shots is to get Rob & Julie in happy, busy moments together. A lot of the smoothness of filming is to do with the talk in between takes. For the actors to be happy they also need to be interested and able to laugh. And they seem to like to listen, too, rather than engaging themselves. Nick is good in these situations because when he chats to them he’s not giving direction at all—that’s Beth’s job. He keeps it light and good-humoured.'

Later, in the library: ‘Rob spends a lot of time sitting on the corner of the desk. He seems to like it there :). Probably helps in giving a natural look … Rob and Julie, now left alone, are discussing the coming exchange together.’

Opera filming 1.01: words

These people and this film equipment are at Lindesay House on Day One for the sole reason that the composer and I wanted our music and words on film. I have total confidence in his music—but when it comes to the words, I realise they are under absolutely pitiless scrutiny. And the scrutiny is mine, because composer and everyone else have their own tough job to do.

As I hear the same phrases from the speaker, time after time after time after time for each shot, I feel the very bones of the work are relentlessly laid bare. Every word—every syllable—counts. If there were a phrase that expressed nothing about the character pronouncing it, or sought no response from another in exchange, or were unreasonably difficult to sing, there would be a fracture in the body of this work that would take prodigies of effort by other people to repair. Words matter. The very concept of this concept film was first given in words!

When shooting is over on Day Three, my fathomless sense of responsibility for those words is matched only by my awe of the artists and technicians who have made them live and breathe. I must simply thank Thalia, the muse of drama, for making me work so hard on the libretto of Émilie & Voltaire.

Shooting Émilie & Voltaire concept film: costume

Brendan de la Hay, designer for the concept film, looked after (and in some cases supplied) the costumes and ‘dressed’ the sets. Here are some thoughts about costume from different moments in my diary.

First, the dress in the opening scenes: 'Julie’s dress, being a pearly colour with open floral pattern (‘parsemée de fleurs!’) in pinks and light greens (+ pink trim at bosom) is not unlike the dress in the supposed portrait of É that we used in the brochure. Funny how things cluster together.'

Later: 'Brendan and Nick showed me a lovely night-dress combination & wondered if Émilie could be wandering around in it, with Voltaire—I said sure. Reminded them of that servant of V’s who published a risqué memoir in which he claimed he’d seen É stark naked ‘comme une statue de marbre’. Probably a lie but people believed it at the time … Why not give ourselves that freedom? It gives lovely variety to the film …

Later again: 'Julie is standing near the end of the sofa in a lovely pink nightie waiting to shoot outside and upset with Nick that they’ll be shooting in the heat of the day. The cranked-up music is deafening! Last shot for Rob. Doing it once more. After a certain amount of discussion about time.'

'Lovely' was obviously my word of the day! You can see that Julie was all smiles for the very sunny shoot in the garden.

Creating a character--a film diary

This week has been filming 1.01 for me. I've learned about the creative collaboration of actor and director, and how the energy of each person goes into the characterisation. Here are some direct quotes from my diary about the creation of Emilie by Julie Lea Goodwin and director Beth Daly.

'They just shot the last few lines of the film on the lawn, in full sunshine. A cluster of figures (and parasols) around the camera and Julie alone on the lawn. Starts with profile towards camera then walks down the garden, followed by camera. Turns slowly and spreads her arms, then delivers the line that brings tears to my eyes every time I hear it--and it did the same to me today even though I was about 30 metres away and the sound was coming from a handheld computer (Kailesh Reitmans). Wow ... Julie looks quite anguished doing the last aria. Real feeling. Beth got as much drama as poss into it and seems to have hit all the right spots.'

The photo shows Beth and Julie together, working up to a scene in the library.

Émilie & Voltaire concept film completes shooting

As the librettist on set I was a mere observer, fascinated to see how a film is shot. Here in the parterre garden at handsome Lindesay House in Darling Point, Sydney, I caught this moment after the camera had been following Émilie around the pebbled pathways as she sang her final aria. Here, as the sequence is played back on the tiny monitor, we see best boy Nathan Niguidila, focus puller Cayla Blanch, composer/executive producer Nicholas Gentile, director Beth Daly (partly obscured), and Émilie herself, Julie Lea Goodwin. In the background on the left is director of picture Aravind Shanavaz and assistant gaffer Steffanie Watson.

Starring with Julie Lea Goodwin in this short film are Rob McDougall as Voltaire and John Longmuir as Maupertuis.

I was overwhelmed by everyone's commitment. Working tirelessly alongside these troupers were producer Demi Louise, production designer Brendan de la Hay, second assistant director Britannie Shipway, gaffer Rupan Poudel, Hair and makeup team Nicola Beverly, Alysha Maree and Renee Matis, sound designer Kailesh Reitmans and stills photographer Reswin Bahas.

In the following blogs I'll share with you some of my notes from those three intense and momentous days.

Julie Lea is Émilie

A joyful day for me: I can share our delight that the wondrously gifted Julie Lea Goodwin embodies Émilie in the concept film Émilie & Voltaire, shooting next week! I've just been replaying her new recording of Émilie's final aria in the film--heart-rendingly beautiful. To introduce the character whom Julie portrays so seamlessly, here is an extract from my notes on the libretto.

In 1733, at the age of 27, the brilliant and beautiful Émilie du Châtelet met Voltaire—at the opera—and they became lovers. She was studying hard in mathematics and physics, and Voltaire paid for her to be tutored by a friend: Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, one of the foremost geometers in Europe. In 1734, disaster struck—a warrant was issued by King Louis XV for Voltaire’s arrest for the publication of a banned book, and he had to go into hiding. He might have fled abroad but instead Émilie offered him secret refuge at Cirey, the Châtelet mansion in the Champagne.

Voltaire decided to renovate Cirey at his own expense. He built a new wing on the building with funds that he politely designated as a ‘loan’ to the Marquis du Châtelet and got government and church permission to live as a ‘guest’ at Cirey, where he begged Émilie to join him. When she did so in June 1735, she wrote, ‘I’ve given up everything to live with the only person who has ever filled my heart and my mind.’

Rob McDougall, the voice of Voltaire

Composer Nicholas Gentile and I are thrilled that the amazing Robert McDougall brings his deeply expressive voice to the role of Voltaire in the concept film of Émilie & Voltaire, which is being shot next week! Voltaire was a beloved and highly experienced man of the theatre, and loved to act out the parts that he wrote for tragedy and comedy on the French stage, to give the actors ideas about interpreting his characters. I think we can be sure his voice was pleasing, flexible and full of expression. He was a passionate and amusing man and his emotions were intense. There is a warmth and depth of feeling in Rob's voice that to me bring the essence of Voltaire into this drama. Here's an extract from my character notes, prepared just after I finished writing the opera libretto in 2018.

Most people recognise Voltaire’s name today and know what he stood for—freedom of speech, tolerance, compassion and social justice. In the early eighteenth-century such notions were seen as subversive, and few of his books got past the royal Censor. Born François-Marie Arouet, he gave himself a fictitious aristocratic surname, ‘de Voltaire’ and became one of the most entertaining, moving and amusing writers of his time. He believed that knowledge and reason should lead people at all levels of society to uphold human rights, and that’s what made him a key figure of the Enlightenment—and a thorn in the side of the government.

When Voltaire met the brilliant and beautiful Émilie du Châtelet in 1733, she became his scientific inspiration. From Cirey, her country mansion where they both lived, Voltaire wrote to a friend: ‘I divide my time between learning about nature and studying history. Twenty-five years are quite long enough to devote to poetry; and to all those who’ve dedicated their springtime to that difficult and delightful art, I recommend that they consecrate the autumn and the winter of their lives to simpler things, which are no less seductive, and which it’s shameful not to know.’ Of course he continued to write superlative plays, poetry and fiction (such as Candide) to the end of his days, but his pursuit of universal truths was genuine.

Theirs was a ‘marriage’ of minds, but there were differences between them. She was a grand lady; he was bourgeois. The riches and luxuries that he lavished on her derived not from noble landholdings but from vulgar commerce. She was a lovely woman in the prime of life; at 44 he was twelve years older than her. And he could not forget the way she had delayed coming to Cirey for an entire year. In Paris and at Versailles she gambled at cards, attended the opera with friends and spent time with her mathematics tutor, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis. In a typical spirit of self-ridicule, Voltaire wrote to a friend, ‘I wait for her with the patience of a cuckold.’

In 1738, with the sudden appearance of Maupertuis at Cirey, it is natural for Voltaire to feel again the fears, misery and jealousy that assailed him during that long year when he lived and worked there alone, waiting for Émilie.

More...

Voltaire to Willem ’s Gravesande, 1737

Voltaire is back at Cirey—what a relief for Émilie! Ah, but can their troubles really be over? Here, Voltaire is struggling to quash fake news following his association with ‘s Gravesande and other Dutch physicists. I usually give you extracts from his correspondence—but this is the whole urgent letter.

You remember, monsieur, the absurd calumny that was going the rounds during my stay in Holland. You know whether our supposed debates over Spinoza and matters of religion have the slightest foundation in fact. You were so indignant about this lie that you deigned to refute it in public: but the calumny has penetrated as far as the court of France, and your refutation has not. Evil has wings, while the good moves at tortoise pace. You wouldn’t believe how people have blackened my reputation to Cardinal de Fleury [the Chancellor] on paper and in person. Everything I possess is in France and I’m forced into demolishing a falsehood that in your country I would be content to despise, just as you have.

Please, beloved and respected philosopher, I beg you to instantly help me make the truth known. I haven’t yet written to the cardinal in my own justification. Nothing can be more humiliating than the position of a man who has to argue his own case; but he plays a fine role who takes up the defence of an innocent man. That worthy role is yours, and I suggest it to you as a man who has a heart worthy of his head. Write to the cardinal: I assure you that two words from you, and your name, will do a great deal—he will believe a man whose custom it is to demonstrate truths. I thank you and I will always remember those that you’ve taught me.

I have only one regret: that I can no longer study under you. However, while I cannot hear you, at least I can read you. Love and truth led me to Leyden; friendship alone tore me away. Wherever I am, I shall always retain the most tender attachment to you, and the most perfect esteem.

Introducing Maupertuis, powerfully performed by John Longmuir!

We will soon be shooting the concept film of our opera Émilie & Voltaire. Over the next three weeks I’d like to give you a glance at my character notes, beginning with the brilliant characterisation of Maupertuis by tenor John Longmuir. His magnificent voice and his gift for passionate operatic roles make him the perfect Maupertuis for the concept film.

1736-7 was the time of Maupertuis’s great expedition, when he became famous in France and throughout the scientific world as ‘the man who flattened the Earth’. He led a team beyond the Arctic Circle, under royal commission, to prove Isaac Newton’s theory that the Earth is relatively flatter at the Poles. In a letter to Émilie, he explained that when measuring the surface of an icy river, he drank cognac, because it was the only liquid that didn’t freeze!

Maupertuis is energetic, decisive, and dedicated to science for its own sake. He’s on a bit of a high when he arrives at Cirey, Émilie’s country mansion. As a member of the French Academy of Sciences, he knows the results of an essay competition that Voltaire and Émilie both entered—and he also knows Émilie’s secret before Voltaire hears of it.

He claims to be a great mate of Voltaire. And how does he feel about Émilie? When she was in Paris, they had a brief affair, but he didn’t let it become too intense because he knew she was extremely demanding. When she chose Voltaire over him, he thought the dangerous dalliance was over. But she has been begging him to visit Cirey—there’s just a chance that she’s tired of living with Voltaire in rural solitude!

Émilie to the Comte d’Argental, February 1737

Monsieur du Châtelet [her husband, the marquis] is pestering me to accompany him to the Lorraine for the princess’s wedding, but I don’t want to have anything to do with it: I’d be miserable at court [at Lunéville] and at a wedding. I can only live in the place where I last saw our friend. They claim in the Gazette d’Utrecht that Monsieur de Voltaire has taken advantage of the weather to go to Prussia. Alas! It might have been quite enough if he’d gone to Lunéville! However, as you say, I must forget about the past and think about snatching what peace I can from present misfortune. Adieu. You are my consolation; when will you be my saviour?

As you may know, when he left he planned to be away two months before his return—simply because he needed that amount of time. Therefore, you can’t say too much to persuade him otherwise; if he got it into his head to have the Philosophy printed, there’d be no end to it—I’d be dead before that.

On the day he passed through Brussels, they put on Alzire [a play that was a hit for the Comédie Française]. His crown of laurels follows him everywhere. But what will glory do for him? He’d be much better off happy and unremarked.

O vanas hominum mentes! O pectora caeca!

[Lucretius: Oh, the empty heads of men! Oh, blind hearts!]

Vale et me ama et ignosce.

[Farewell: love me and forget me.]

Voltaire to Nicolas-Claude Thiériot, from Holland, early 1737

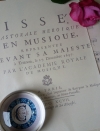

Émilie du Châtelet’s favourite opera composer was Destouches, and Émilie loved to play and sing his Issé at the harpsichord. She often gave the whole opera for guests. It’s unlikely that she would have felt like singing, however, had she seen this letter written by Voltaire while she waited for him to return to France. It sounds as though Holland suits him much better than Cirey.

The Crown Prince has commanded Count Borck, ambassador for the King of Prussia in England, to offer me his house in London, should I wish to go there, as rumour has it at present; however I’m being treated here very much better than I deserve. The bookseller Ledet, who has earned a little by publishing my feeble works, and who is now bringing out a magnificent edition, shows his gratitude to me in much greater measure than Paris shows its ingratitude. He insists that I stay with him when I go to Amsterdam to see how Newtonian philosophy is faring. He has chosen to place the head of your friend Voltaire on his masthead. Due modesty prevents me from telling you in all sincerity what boundless consideration I’m shown in this country.

I don’t know what impertinent rag, wretched echo of the wretched news penned in Paris, took upon itself to say that I’ve fled abroad so I can publish without licence. I’ve denied this fabrication in the Gazette d’Amsterdam by disowning everything of the sort that’s been printed in my name, whether in France or abroad. I acknowledge as mine only works that have received a royal licence or official authorisation. I’ll confound my enemies by giving them no hold on me, and I’ll have the consolation that whoever wants to harm me will have to lie outright …

In the breaks allowed from philosophy I’ve been correcting all the poems I’ve written from ‘Oedipus’ to ‘The Temple of Friendship’. There will be several addressed to you: over these I’ll take greater care.